As everything changes in this world, so does the profile of art collectors. The classic picture of the mature magnate bidding for a Rothko at a London auction room is giving way to that of young individuals in their early thirties who invest from their mobile phones, share online stories of their favorite art stands from the Frieze Seoul fair, and buy and sell digital art with the joy of someone who accepts that everything in this life is transitory, so that leaving a legacy is not a priority. The “society of the spectacle” predicted by the philosopher Guy Debord is now functioning at full capacity, while social media and their algorithms impose new customs on us. And new customs require new terms to designate them. For the art market, this change implies the transition from the era of the blue chip to the era of the red chip.

This was pointed out by art columnist Annie Armstrong in a widely read article in the industry, published last spring in the specialized magazine Artnet. Under the title Forget Blue-Chip Art. It’s a ‘Red-Chip’ Art World Now, Armstrong detailed what this cultural shift entails. It is an art market that, in its most substantial segment (at this point it’s worth remembering that most of the art for sale falls far short of this privileged position), had for decades been dominated by the undisputed big names, the so-called blue chips: artists legitimized by the power of institutions, with stratospheric and ever-rising prices. But the market is rapidly evolving towards another concept, that of red chips, which is closer to the visual and conceptual schemes with which a new generation of collectors feel more comfortable.

The ‘red chip’ art would be visually striking, but with a not too complex conceptual background.

Miguel Ángel García Vega, an expert on art market issues, sums it up this way: “We’ve been using the term blue chip for many years, with buyers acquiring art that was harder to understand and required more effort. Now there’s another generation, which will be the one to inherit the most money in history, that seeks a much simpler artistic expression. Art is a reflection of the society we live in, and this one wants fewer complications and lots of experiences, to live in the moment.” That’s what the red chip universe is all about.

Naturally, the prevailing political and economic situation at any given time also influences art. So it’s hard not to consider the current rise of far-right governments and rampant capitalism as additional factors. In this regard, Annie Armstrong’s article timidly mentioned Donald Trump: “[Red-chip art] is not unrelated to Trumpism, and Trumpism’s aesthetics, but it does not have an explicit political stance,” the author states.

Blue chips are the paintings of Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer, or of Julie Mehretu and David Hockney, the photos of Cindy Sherman and the sculptures of Yayoi Kusama.

However, it is significant that art had already borrowed the old label “blue chip” from the financial world, which in turn had it from gambling. While blue chip originally referred to stock market investments in companies of proven solvency, which generate abundant dividends and guaranteed capital gains, the expression comes from the blue chips used in casinos and card games, considered to have the greatest economic value. It is important to note that, when applied to the artistic world, it does not identify a movement or specific forms of expression, but rather is a market term. For contemporary art, therefore, “blue chips” include the paintings of Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer, or Julie Mehretu and David Hockney, the photographs of Cindy Sherman, and the sculptures of Yayoi Kusama, as well as the galleries that sell them, such as Hauser & Wirth to Gagosian, from Pace to Thaddaeus Ropac to David Zwirner. Safe bets, known to a wide audience and extraordinarily expensive, they remain within the reach of a select few who—notwithstanding any genuine appreciation they may have for the art they collect—are proud of their possessions and the symbolic status they confer.

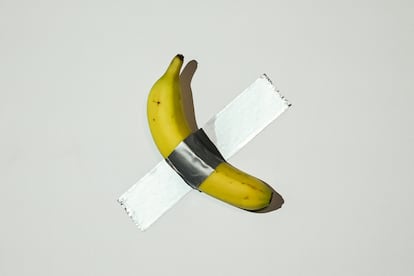

From these parameters, it’s easy to identify a blue-chip artist. Things get a little more complicated when we try to do the same by shifting to red. For this, we can turn to creators close to the aesthetics of Japanese anime or classic Western comics, graffiti and street art, and also those who have survived the collapse of the NFT phenomenon. In some cases, their high prices make them almost indistinguishable from their older blue-chip siblings, but in others, their quotes are much more modest. At various points in her article, Annie Armstrong brings up a fairly heterogeneous group of red-chip artists, including, among others, Yoshitomo Nara, Beeple, Mr. Brainwash, and KAWS, as well as pieces such as the dubious sculptural portrait that Mark Zuckerberg commissioned of his wife, Priscilla Chan, from the American artist Daniel Arsham. They all have in common the fact that they constitute visually striking art, with a conceptual background that is not too complex, although this latter is debatable in the case of Yoshitomo Nara (not so in the case of his many imitators). Even more debatable is the inclusion in the group of the Italian conceptual artist Maurizio Cattelan −thanks to his famous work Comedian, a very expensive banana acquired and then eaten by a collector with a cryptobro profile−, whose sharp critique of the art market and late-capitalist society should place him in a different spectrum, regardless of the type of collectors he may eventually attract.

Victoria Solano, who has a long career as a gallerist in leading international venues such as Marian Goodman (in New York), Travesía Cuatro, and Carlier Gebauer (in Madrid), and who is currently an independent consultant and art dealer, believes that the red chip concept does offer some utility: “It helps us understand a way of approaching the contemporary art market. The red chip buyer is an undeniable trend, one that is very identifiable and that we have seen emerge and grow over the last 10 years. It includes buyers who have made a lot of money from the crypto and tech world, but not only that: we must also consider a type of buyer who generally has no intention beyond the ephemeral, beyond what is hot at the moment. One who does not have a deep, long-term vision, but who suffers from a kind of artistic FOMO, in addition to the aspirational motivation that has always existed in art purchases.” As for artists, Solano believes many of them feel comfortable in this category because it allows them to succeed without being validated by institutions. “Here we can include everyone from established artists to very young content creators who are more in tune with the popular culture of today’s digital age,” she adds.

Another gallery owner, Pablo Flórez, who runs the prestigious Madrid establishment Ehrhardt Flórez, has internationally successful artists on his roster, such as the Secundino Hernández or André Butzer, to whom the red chip label might be applied, but also others with a radically different profile, either due to their long history of successes along the “blue path” (such as Imi Knoebel) or the complexity of their artistic expression (David Bestué, June Crespo). So Flórez makes it clear that his gallery has no intention of flirting with the red chip. “The cases of artists who have been successful in recent years, and not so recent, such as Secundino Hernández or the André Butzer phenomenon, presumably have nothing to do with these very specific market trends,” he believes. “Butzer’s language and his reflection on popular culture in relation to Expressionist painting date back to the late 1990s, for example. As a gallery, we believe we must be a space of resistance to these dynamics that impoverish our culture and, in the long term, also hinder the industry as a source of wealth.”

Victoria Solano agrees: “I’m concerned that some galleries have succumbed to the temptation of prematurely and artificially inflating the prices of young artists, jumping on the bandwagon. This not only harms the market but, above all, the artists’ careers. I believe in building and developing their careers more organically, rather than through flash-in-the-pan. An artist’s career should develop over a long period of time, and that’s the opposite of fleeting fads.”

However, Pablo Flórez doesn’t find that there has been a widespread negative trend, at least from what he’s been able to see. “The collectors we work with generally have a different perspective, and they collect out of passion or pleasure,” he asserts. “Yes, some requests from foreign buyers have a certain speculative tinge, but they don’t have an impact on our numbers or our work. On the contrary, I’ve noticed an evolution in Spanish collecting, with people with a long tradition of collecting responding very positively to the new languages and trends emerging in our country, and on the other hand, new collectors or buyers who are gradually incorporating contemporary art into their lives. That said, we can’t deny that there are always exceptions: people looking for a quick investment in contemporary art. But we’ve been experiencing this trend at the gallery with some artists for over 15 years now.”

Perhaps the weak point of these so-called red chips lies in their intrinsic quality. “My opinion is that the vast majority have a residual quality, because they lack a critical element,” says Miguel Ángel García Vega. “But we must keep in mind that mistakes are also part of museum collections. We tend to think that they’re all about Goya, Velázquez, Ribera, and Zurbarán, but that’s not the case: in between, there have been dozens of artists who were there but who, over time, have faded into obscurity.”

In any case, whether they’re dealing with blue or red chips, art market players don’t follow very different patterns in their decision-making, and their collections tend to converge around a few names with a certain aura. “In this regard, I like to quote a passage from Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich that a collector friend of mine always reminds me of,” notes Victoria Solano. “It says something like Ivan Ilyich had decorated his house with such an intention to be original that it ended up resembling any other of its kind.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition