A team of scientists from the Department of Physics at King’s College London has discovered a set of mathematical equations that makes it possible to build a clock from any…

An international team of researchers has discovered that a marble head found in 2003 belonged to Laodice, a woman of the elite of ancient Chersonesus who played a key role in securing the city’s political freedom.

In 2003, during excavations in the ancient Greek city of Chersonesus Taurica, in present-day Sevastopol (Crimea), a team of Ukrainian and Polish archaeologists made an exceptional discovery: the incredibly well-preserved marble head of a woman inside a Roman house. For more than two decades, an interdisciplinary group of scientists has worked to unravel its secrets. Now, at last, they can tell its full story.

The sculpture, which turned out to be a portrait of an elderly Roman matron, was not just another piece. It was found in a clear archaeological context, something extremely rare in this type of find, which allowed the researchers to date it with unusual precision.

Through the combined use of radiocarbon dating techniques, isotopic analysis of the marble, microscopic studies of the patina, and a meticulous examination of the tools used to sculpt it, the team was able to determine when and where it was made, and also to identify with a high degree of certainty the person represented: a woman named Laodice, a member of one of the most influential families of the city in the 2nd century AD.

Chersonesus was no ordinary city. Founded by Greek colonists in 422/421 BC on the southwestern coast of Crimea, it eventually became a crucial strategic point for Rome in the Black Sea region. Although it was never formally annexed, the city reached an agreement with the Roman Empire, obtaining the status of eleutheria (free city), which allowed it to maintain nominal autonomy but under the watchful eye and strong political and economic influence of Rome.

Real power lay in a few wealthy and influential local aristocratic families who maintained close ties with Rome. It was in one of these luxurious residences, a large 718 m² house near the city’s theater and agora, that archaeologists Elena Klenina and Andrzej B. Biernacki found the sculpture.

The head was discovered in a semi-basement room (room 16). Archaeologists determined that, around the second half of the 2nd century AD, this space had been filled with earth and debris to raise the floor level. Within this compact, yellow-brown fill layer, the marble head appeared, along with a coin from the 3rd–2nd centuries BC, a ceramic altar with figures of Artemis and Apollo, and various pottery fragments.

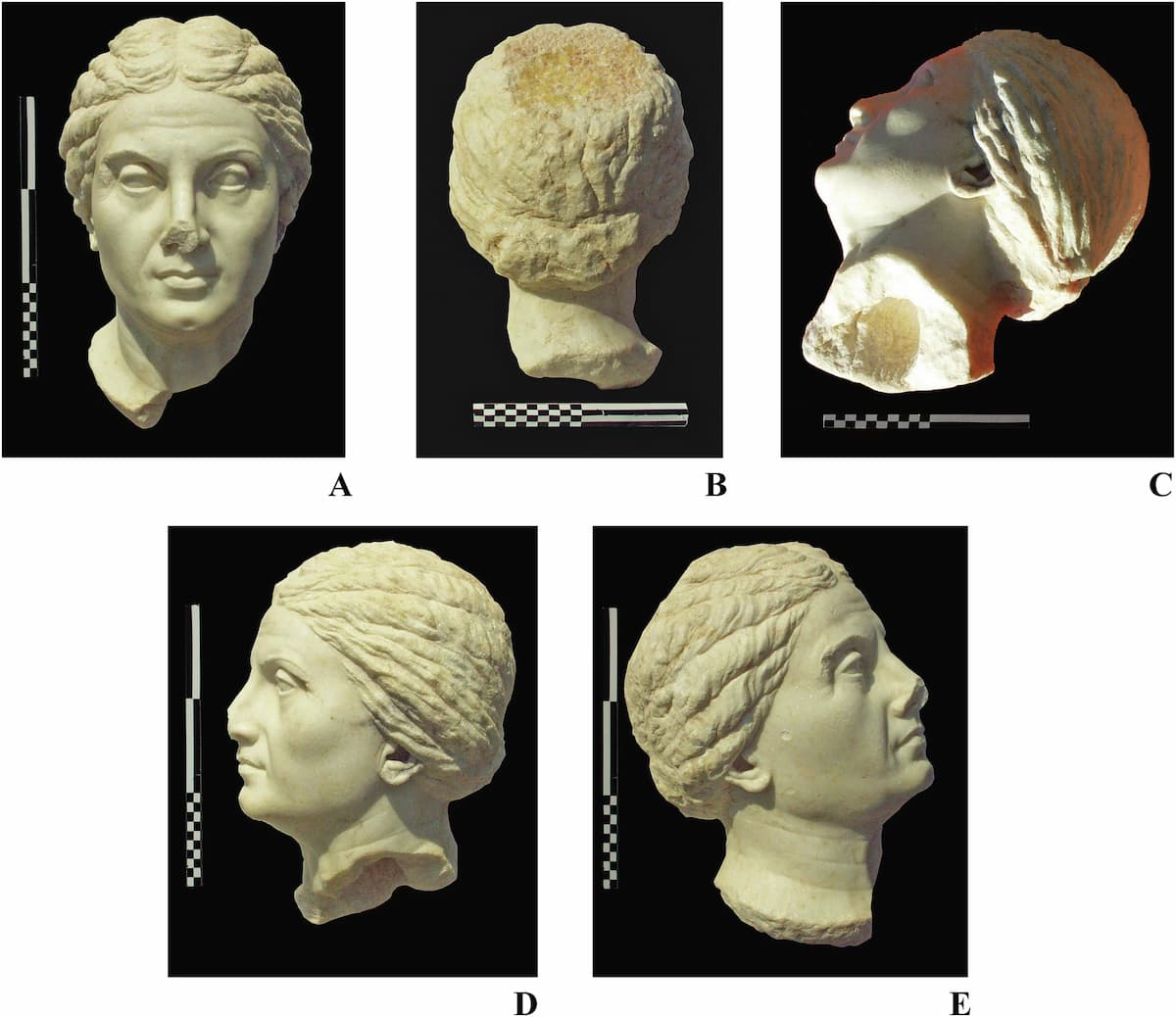

The sculpture, which preserves the lower part of the neck, was broken on the left half. The tip of the nose was also missing, and there was damage to the right eyebrow and cheekbone. Analysis showed that this damage was ancient, prior to its burial, since the edges of the breaks were rounded and covered with the same light ocher patina as the rest of the piece.

A crucial detail was the discovery on the back of the head of a flat, rough surface cut diagonally. Researchers explain that this area, with marks made by a pointed chisel, was prepared to glue a piece of marble to repair a defect or crack in the original stone, a restoration technique known since the Greek Archaic period. Likewise, the base of the neck had a circular hole designed to insert a metal dowel (a pin) that would attach the separately carved head to the torso of the complete statue.

To solve the mystery of the lady’s identity, the scientists acted like detectives, employing various forensic techniques applied to archaeology.

Radiocarbon dating of charcoal found in the strata associated with the head helped narrow down its chronology. The results indicated that the house was remodeled and the room filled in during a period between 60 and 240 AD. This placed the moment when the sculpture was deposited there at the end of the 2nd century AD.

Stable isotope analysis of the marble was essential to determine its provenance. A small sample of the sculpture revealed a unique isotopic signature. By comparing it with Mediterranean quarry databases, researchers were able to identify the origin of the stone with astonishing precision: it was lychnites marble from the Greek island of Paros.

This marble was famous in antiquity for its pure whiteness and translucent quality, which made it appear to radiate light, hence its name, related to the Greek word for “lamp.” It was an expensive and prestigious material, reserved for high-quality sculptures, already indicating the high status of the person portrayed.

Microchemical and X-ray fluorescence analysis of the patina layers and the joining surfaces sought to identify the adhesive used to fix the repair piece or attach the head to the torso. Although iron and silicon compounds were detected, it was not possible to identify with certainty the nature of the original organic binder. However, traces of a red iron oxide pigment were found, which may have been part of the joining mortar or the result of a fire that oxidized the materials.

Traceology, or the study of tool marks, allowed reconstruction of the carving process. The researchers identified up to eleven different tools used by the sculptor: pointed chisels, flat chisels (5 to 12 mm wide), round chisels, toothed chisels, as well as scrapers and abrasives such as pumice stone for the final polishing.

The analysis identified several stages in the carving process of the woman’s marble head, the study explains. The first was rough shaping with a pointed chisel, followed by the use of flat and round chisels to shape the hair. The marks of these tools are especially visible on the back of the head, which was less worked because it was intended to remain hidden in a niche. The fineness of the frontal details contrasts with the coarser work at the back, a common practice in ancient sculpture.

Artistic and iconographic analysis of the portrait reveals an elderly woman with a serene and elegant expression. The sculptor skillfully combined two traditions: the typical realism of private Roman portraits, which shows the signs of age on the sides of the face without idealization (folds, sagging skin, “decrepit” ears, and neck wrinkles), with the softening idealism of the Greek tradition, which beautifies the frontal features, softening the forehead wrinkles and elegantly defining the mouth and eyebrows.

The hairstyle is another key indicator. The woman wears a variation of the “melon” hairstyle, very fashionable among high-status women in the Greco-Roman East during the 1st to 3rd centuries AD. This style, which divides the hair into coin-like sections gathered in a bun at the nape, is here combined with two flat waves on the forehead, a feature associated with portraits of empresses such as Faustina the Elder.

The combination of these stylistic elements—the Romanizing realism, the Greek idealism, the modified “melon” hairstyle—led the researchers to date the sculpture to the mid-decades of the 2nd century AD, probably during the Antonine period or shortly afterward, and to conclude that it was produced in a workshop in the eastern provinces of the Empire or by craftsmen trained in that tradition.

All the material and stylistic evidence pointed to the portrait representing a woman of the local elite of Chersonesus. But the final step in naming her came from epigraphy.

The researchers turned to inscriptions found in the city. One of them, engraved on a marble pedestal, honored a woman named Laodice, daughter of Heroxenos and wife of Titus Flavius Parthenocles. This man belonged to one of the most powerful families of the city, who had obtained Roman citizenship under Emperor Vespasian. The inscription, dated to the second quarter of the 2nd century AD, indicates that the city erected a statue in honor of Laodice for her services.

What did Laodice do to deserve this honor? The researchers connect it to the most important political event in the history of Chersonesus at that time: obtaining eleutheria (free city status) from Rome. Epigraphic sources mention several embassies to Rome to obtain this coveted status. One, around 138 AD, failed. Another, sent to Antoninus Pius, succeeded, and it is believed that the city was officially declared free no later than the 140s AD.

The study concludes that Laodice participated in the effort to obtain the eleutheria, which was the reason for erecting the statue with an honorific inscription on the pedestal according to the decision of the city authority. Although the exact nature of her participation is unknown, the fact that she was honored with a public statue suggests that her role was perceived as crucial.

The sculpture, about 25 cm high, was part of a full-body statue that must have been about 2 meters tall, a size clearly intended for display in a monumental public space, such as the city’s agora. Its presence in a private house is explained by the fact that it was moved there as fill material after the destruction or abandonment of its original location, probably after the statue was dismantled and decapitated.

The portrait of Laodice is tangible testimony to the active role that some elite women could exercise in Roman politics and society, even in distant provinces. Her story, recovered thanks to two decades of meticulous interdisciplinary research, sheds light on a crucial moment in the history of Chersonesus and demonstrates how modern science can give voice and face to individuals whose achievements were on the verge of being lost to time.

As the authors note, the findings of this study have shown that matrons exercised significant influence and played an active role in political life, both within the confines of Rome and beyond its borders, in the first centuries after Christ.

Klenina, E., Biernacki, A.B., Claveria, M. et al. An interdisciplinary study of an unknown Roman matron’s sculpture portrait from Chersonesos Taurica. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 400 (2025). doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01975-6

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.