The examination of form and function is a key component of the artwork created by world-renowned British-born sculptor Tony Cragg. His highly abstract pieces heighten not only the viewer’s awareness of their own relationship to the material world, but also to their immediate surroundings. Recently, the artist made his Thailand debut with the unveiling of a massive stainless-steel sculpture that will be on permanent display at One Bangkok.

(Hero image: Artist Tony Cragg, Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London, Paris. Salzburg, Seoul. Photo by Charles Duprat)

Tony Cragg is an artist who explores the complex relationships between the natural and man-made world, creating innovative, distinctive sculptural pieces along the way. A self-described “radical materialist”, he says that he is “interested in the internal structures of material that result in their external appearance”.

Although born in 1949 in Liverpool, in the United Kingdom, Tony currently lives and works in Wuppertal, in Germany. Since the 1980s, his work has been shown at important international exhibitions, including documenta in Kassel (1982 and 1987), the British pavilion at the Venice Biennale (1988) and the São Paulo Biennial (1983). He was awarded the Turner Prize in 1988, made a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres by France in 1992, and received Japan’s prestigious Praemium Imperiale in 2007.

In his early works he used a lot of found objects, later applying the same stacking principles to thin layers of wood to form undulating organic structures. These works recall natural geological forms, such as the sedimentation of mineral particles that create rock strata. His more recent works, by contrast, suggest the movement and transience of elements caught in the process of transformation, as in stainless steel forms that convey the fluidity of molten metal.

One of these “molten metal” sculptures is now on permanent display at One Bangkok, a cutting-edge mixed-use development in the city’s CBD which consists of residences, office space, multiple hotels, a shopping plaza, and no shortage of dining spots. Interestingly, a large portion of the One Bangkok property has been set aside for public use, in the form of green spaces, but there’s also what’s called the ‘Art Loop’, a vibrant route spanning over 2 kilometres throughout the project, featuring diverse artworks and creative programs. And it’s here that this new work by Tony Cragg finds a home.

The piece – which stands several metres high – is also doing double duty as an official exhibit in this year’s Bangkok Art Biennale (BAB). As such, the biennale organisers recently brought this celebrated artist to town, not only to oversee his work’s installation at One Bangkok, but also to do a public lecture at the Queen Sirikit National Convention Centre. As for the super shiny sculpture itself, Prof. Dr. Apinan Poshyananda, the Chief Executive and Artistic Director of the BAB, described it to the audience as “hypnotic”.

“The placement of the sculpture is so dynamic that when you confront it from far away, and then you walk towards it, it really pulls you in,” he said. “And as you get close and closer it becomes absolutely amazing!”

For his part, Tony shared with the audience details of his own fascinating artistic journey; from his early days growing up in an engineering family, to becoming one of the most celebrated sculptors of our time. His insights and observations reminded everyone that art is as much about pushing boundaries as it is about telling stories, and that those stories can be found in even the most ordinary objects around us.

“My father worked as an engineer and designed electrical parts and components for aircraft, and this was very influential on my life,” he said, recalling his early years in the UK. Later on, in his teens, he had the opportunity to work as a laboratory assistant – around 1968-69 – and while he enjoyed the work, he relieved the periods of boredom on evenings and weekends by trying his hand at drawing.

“It’s something I found totally fascinating, but I didn’t know anything about art, which I think even today has been a great advantage.”

His girlfriend at the time said the drawings weren’t bad, and that maybe he could pursue something in that direction. “I applied to an art school, and got in,” he went on to say, “and spent a fantastic year in the west of England in a wonderful situation, and for the first time I met people that were interested in art.

“I just really wanted to draw and paint, but then at one point in the middle of the year we were told that ‘next week you’re going to make a sculpture’. I thought that was a terrible idea. I couldn’t imagine what the point of that would be. So, I rather unwillingly started to make a sculpture on a Monday morning and if there was ever a real catharsis in my life, I think it was that moment.

“I realised that doing art in three dimensions is a really ecstatic experience. To suddenly change the volume of something, or the silhouette or texture, and all the time you’re in a relationship, and the ideas are flowing instantly and quickly through your body, your mind, and your emotions… it’s a real trip in some ways. That was 55 years ago, and I’m still doing it.”

He then went on to name some of the prominent figures in the UK sculpture scene who had a definite influence on his own approach to the artform, including established icons such as Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Anthony Caro, and Philip King, as well as the next generation of creative talents, including Richard Long, Barry Flanagan, and the collaborative art duo Gilbert & George.

“The debates and discussions that went around the work were really infused with a lot of energy,” he remarked. “I realised that sculpture was not just about making interesting things in the world, or making things look better. It had really serious issues too. So the discourse and the debate about the work was very, very energetic.

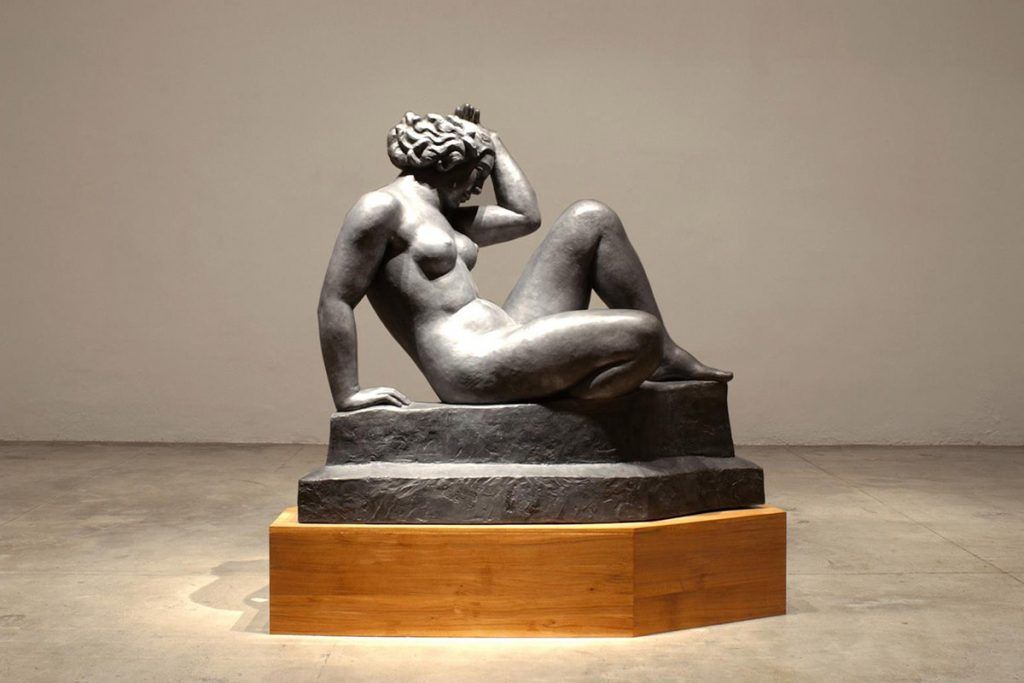

“In Europe all sculpture had been figurative up to the 19th century. It had all been about the human figure. Even if it was made up of animals, they were metaphors for some human condition. At the end of the 19th century, a few sculptors began to change that situation. One of them was obviously Aristide Maillol, who still worked with the figure but he made a kind of composition of geometric forms. He didn’t worry about the eyebrows, and the details of the fingers. He presented the figure as a kind of more stoic and volumetric form.

“Then there was Rodin, obviously, who was a fantastic character because for the first time he wasn’t worried about representing the anatomy in a precise way, or if all the muscles and bones were in the right position. He wanted to have an emotional effect in the work.”

Tony then went on to discuss the revolutionary effect Marcel Duchamp had on the art world, citing in particular the famous incident in 1917 when Duchamp exhibited an upside-down urinal in the “unjuried” Society of Independent Artists’ salon in New York, cheekily giving it the title ‘Fountain’.

“Maybe it was just a sort of a naughty gesture, but the consequence of it was very interesting because what it did is it suddenly made people realise that everything, even a pissoir, or a bar of soap, or a chair, or a glass, or a carpet – everything has a meaning to us. It made us realise that we are in a constant dialogue with materials, and that the material world is influencing us permanently.

“Duchamp taught me that if a urinal can be art, then my kitchen junk can definitely join the party!”

Among the many other topics Tony touched upon during his one-hour-plus talk and Q&A session was how he uses materials like stainless steel and bronze to reflect the modern industrial world. And how, as an artist, he believes in the power of curiosity and creativity to reshape our understanding of everyday objects. In a nutshell, his philosophy is that art isn’t about perfection or imitation, but about envisioning new forms and ideas that challenge how we see the world.

“Art isn’t about mimicking nature; it’s about bringing to life something completely new. I think art is something for the future, and will become more important in the future. And I think we should cherish that.”

(some quotes have been edited for clarity)

The information in this article is accurate as of the date of publication.