‘There is a quieter tradition going on, different artists deciding there’s something really interesting in this room to paint, rather than outside of [it],’ says Scottish painter, Andrew Cranston. ‘Philosophically, you can only be in one place at a time, and we spend a lot of our lives in rooms, or in limited spaces. I think there’s a disease, a paranoia, that you’re missing out on something over the hill, or a party in the next room. It’s a simplistic thing but there’s some truth in it – it is almost like all the world’s problems stem from a person’s inability to be happy in their own room.’

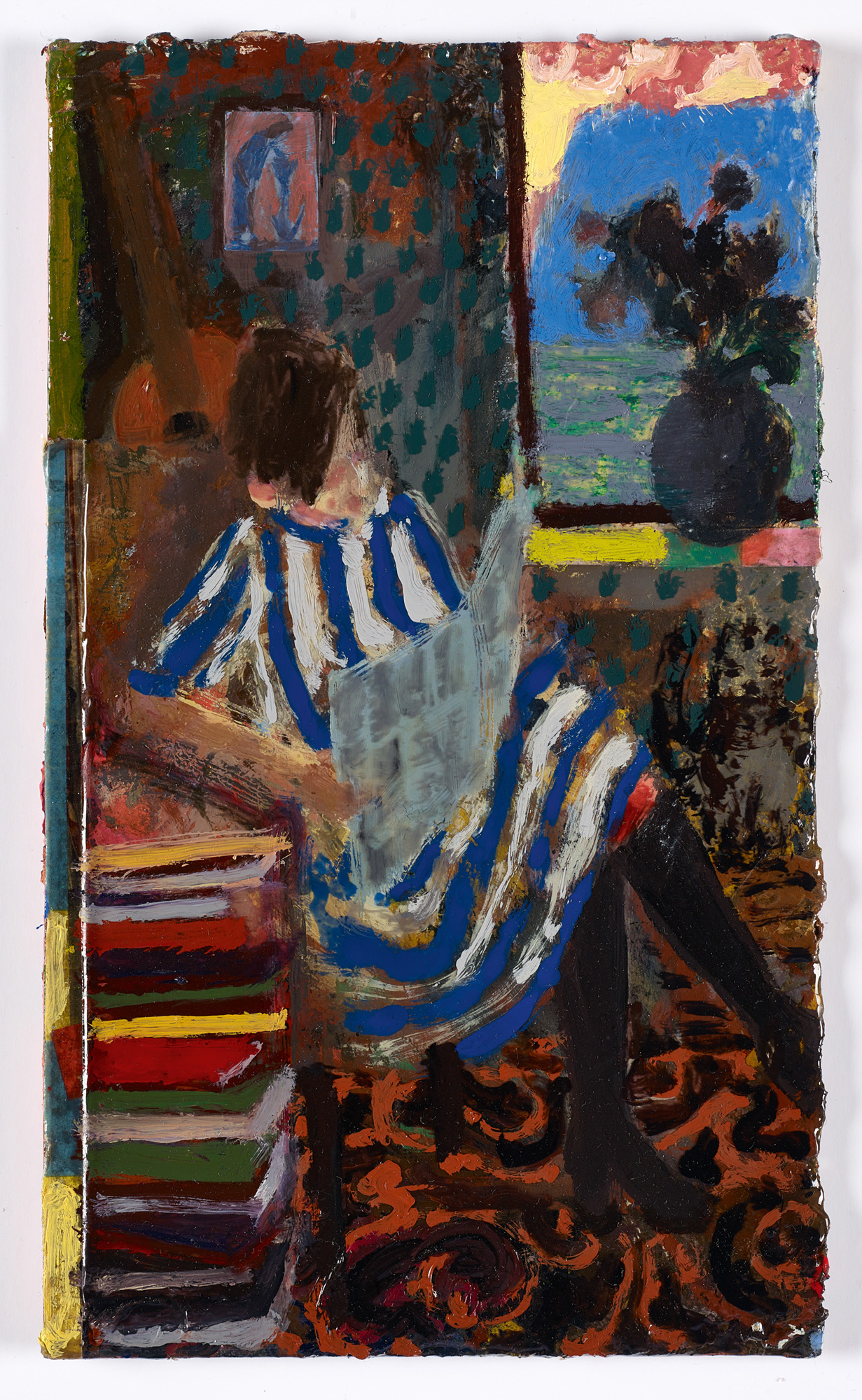

Cranston, born in 1969 in Hawick, Scotland, and based in Glasgow, draws on an art education that concluded with postgraduate studies at the Royal College of Art, where he was taught by Peter Doig, among others. He has been preoccupied with the magical ordinariness of interiors throughout his career, capturing everyday details – food strewn on a table, a quiet moment with the paper – in lusciously thick sweeps of oil paint. Cranston’s work, although firmly rooted in the real world, is nonetheless possessed of a dreamy, otherworldly quality that intersperses memories with mundane details.

Reader, 2018, by Andrew Cranston

(Image credit: Photography: John McKenzie, courtesy of the artist and Ingleby, Edinburgh)

Melons and Heads, 2017, by Andrew Cranston

(Image credit: Photography: John McKenzie, courtesy of the artist and Ingleby, Edinburgh)

‘The condition of a dream is something I can really draw into,’ says the artist. ‘It takes you away from a certain kind of logic, and gives you freedom, but I don’t see it as surrealist at all. It seems more of a concrete kind of fantasy, in the way in which dreams are a part of our everyday life. I do gravitate towards things that have a slightly other quality, where there’s a moment when something’s crystallised. It could be a strange light or atmosphere, or something which could only be described as dream-like. I’m not interested in drama. It’s that moment where there’s a certain feeling of stasis, that feeling that maybe something’s about to happen, or [has] just happened, but it’s not the event itself. If it was a film, you have to have those performances that don’t drive the story forward. They are seemingly unimportant, just little deviations from the story.’

By making the deviations from the story the story itself, Cranston is tapping into a long tradition of observing the unremarkable, a movement in art history that can be traced back to the 17th century and what is now termed the Dutch Golden Age. The period saw an extraordinary flourishing across art and science in the Netherlands, a movement that took shape in the work of artists, notably Rembrandt, Johannes Vermeer, and Frans Hals. They began to consider the realism of interiors as worthy subjects to paint alongside the more accepted biblical scenes and portraits. In the work of their contemporary, Judith Leyster – the majority of which was attributed to Hals until relatively recently – the emphasis on light and shadows inspired by Caravaggio lent a drama to domestic scenes.

Self-portrait, c.1630, by Judith Leyster

(Image credit: Judith Leyster)

It was a tradition that grew stronger over the subsequent centuries. Pierre Bonnard’s bold use of colour in his interiors led the drive into modernism, while in the 19th century, Édouard Vuillard challenged the Parisian stereotype of the domestic as a space reserved for the feminine. His claustrophobic, crowded interiors, juxtaposing patterns with flat planes of colour, bring a jarring realism to everyday scenes, surprisingly intimate in their faithful renderings.

These small details and unexpected clashes in form lend a subversive notion to the formerly female world of a family’s interiors. ‘The idea of interiors as a subject to paint probably didn’t occur to me until I was a parent myself,’ adds Cranston. ‘In a way, the children force you inside, and it’s more domestic, and then you often start looking around you to see if there’s some material there. It was almost art following life, and that interest in in-between and negative, spaces.’

Unseen spaces and unseen work are immortalised in art and elevated into the sacred – a formerly unthinkable move. ‘An observation I have made about art, and with many things, is that the big things, the huge messages of great importance, sometimes didn’t really affect me that much. And yet, the so-called small, unimportant things or the domestic, have the biggest emotional and influential effect on me,’ adds Cranston.

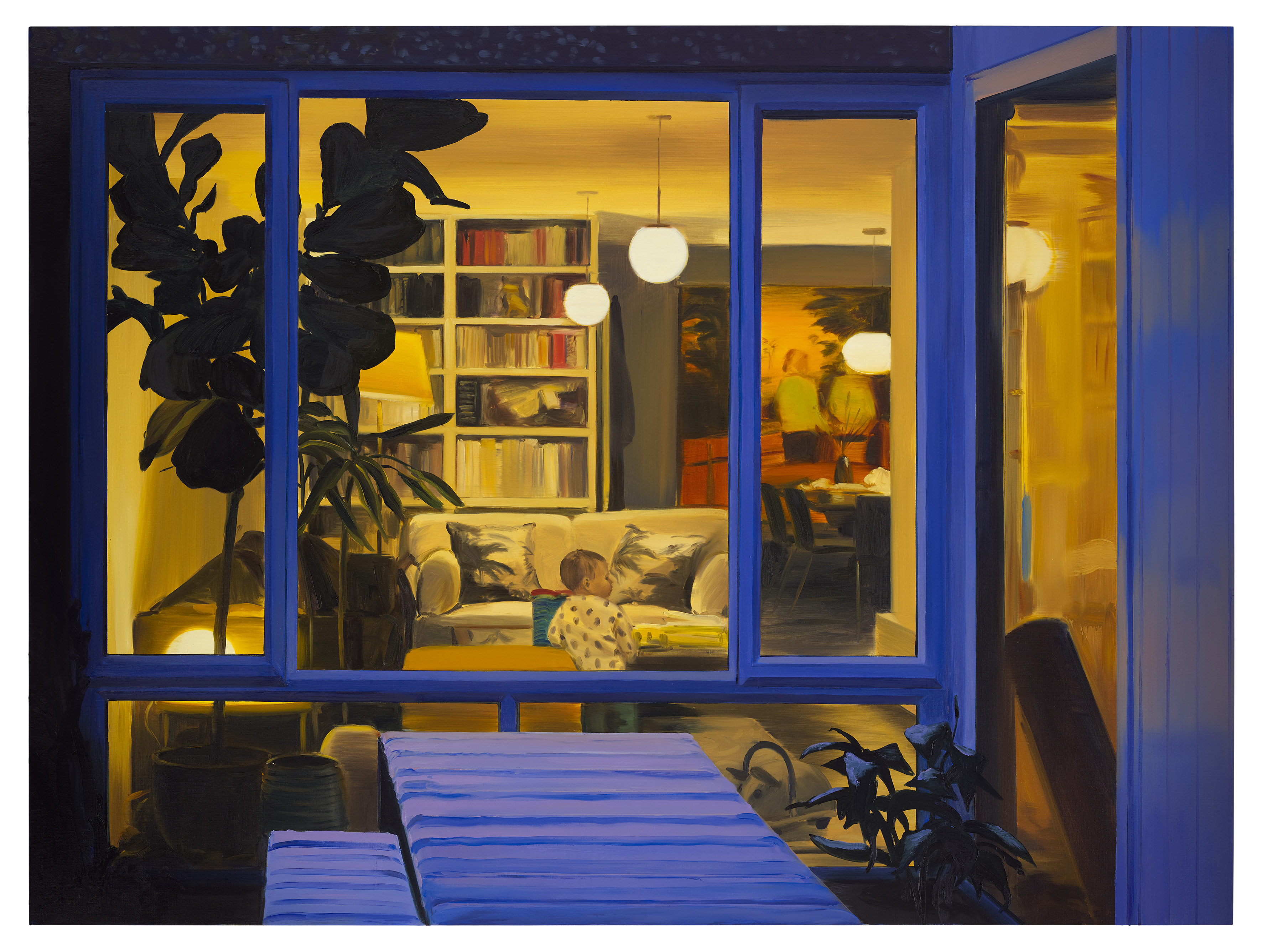

Daphne, 2021, by Caroline Walker

(Image credit: Caroline Walker and courtesy of gallert)

Contemporary female artists are also capturing the subtleties in the silent emotionality of the everyday. Alabama-born, New Jersey-based Danielle Mckinney’s portraits of solitary women have seen a rapid rise for the artist, who first published them on her social media a little over four years ago. In her seductive interiors, we view her women voyeuristically. At leisure, reclining against patterned wallpaper, or sunk into deep velvet sofas, or napping in crisp white sheets, they are martyr-like against the deep dark background from which they emerge. Red lips and red nails, cigarette often in hand, the glimpse we are awarded into her solitary female figures at rest feels incredibly intimate.

Scottish artist Caroline Walker (whom we recently interviewed about her show at The Hepworth Wakefield, until 27 October 2025) draws on her own photographs as the sources for her paintings, which capture the everyday lives of women, whether at home, in the maternity unit or at places of childcare. Her depictions of home are more crowded, usually jammed with the paraphernalia that comes with babies and young children – breast pumps, sticker books, endless washes hung out to dry – but are just as cinematic in capturing the detail in those endless, fleeting days at home with small children.

A theatrical aspect is also present in the homes depicted by Cece Philips (on show at Hauser & Wirth London until 20 September 2025), which invite a contemplation of the interiority of her figures. Drawn in deep colours and often framed in the architectural angles of windows and doors, they are caught as if on stage. Inspired by what the interiors of Dutch Golden Age paintings revealed about their inhabitants, she looks to Vermeer and to the intermingling of foreground and background in Pieter de Hooch’s work, where a painting becomes synonymous with a set.

Nourishing Loneliness, 2025, by Cece Philips

(Image credit: Courtesy of Cece and Almine Rech)

‘Situating my figures within the context of interior scenes is a way of exploring identity and emotion, without depicting them totally or explicitly through the figure,’ Philips says. ‘I’m particularly interested in duality and the line between the private and the public self. The domestic spaces I paint act as a backdrop that is active and emotionally charged – they become metaphors for the inner lives of the figures. In certain ways, the spaces we occupy can act as a reflection of that internal world – and I think a lot about atmosphere when I paint, like a kind of pathetic fallacy, the room takes on the mood of the person, or perhaps the other way around. Colour is central to that for me, conveying emotion in the work with the same weight as the body language of a figure can. Through the rooms the characters inhabit, I’d like the viewer to sense something of that inner self, while also keeping parts deliberately out of reach through framing and details, like their eyes, that are harder to read. I want the viewer to feel like they’re looking in, but not entirely welcome. That distance becomes a quiet assertion of privacy and of the intangibility of their interior.’

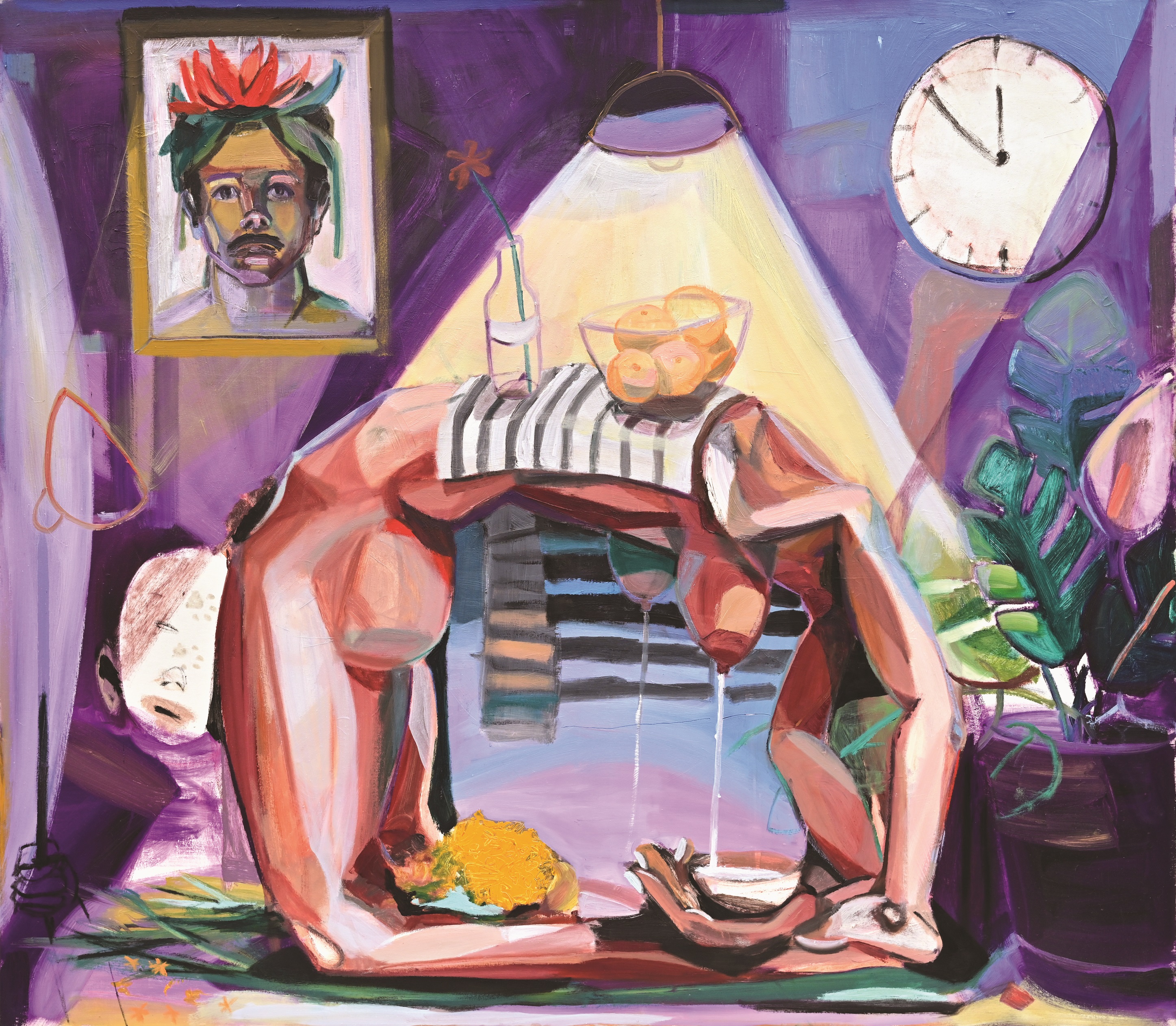

More avant-garde interpretations see the figures and the home become, unsettlingly, one. In Nina Raber-Urgessa’s work, the female body literally contorts itself to fit into the space available to it. ‘The home and the domestic area is a very important place, and there is the struggle between work, home, society and expectation,’ she says. ‘The changing point for me, as a woman, was becoming a mother, and discovering in the modern world that there are these invisible struggles women are having, day by day. They have to remove their body and twist, and distort, to fit. You make sure you create a safe space for your family, for your children, and also for yourself.’ In her work Terepeza (2022), the woman’s body is not just the safe space but also the shelter and the nourishment, the kitchen table itself from which to eat or huddle underneath.

Terepeza, 2022, by Nina Raber-Urgessa

(Image credit: Courtesy of the artist)

In Henni Alftan’s work, home life is fragmented, or cropped in such a way as to create tension, her narratives interrupted or left frustratingly ambiguous. In the geometric blocks of her cityscape, flat planes of primary colours distort and create a separation between our reality and our experience of viewing the work.

For Koak (also showing at Hauser & Wirth London this September), the familiar motifs of home – stairs, flowers, chairs – are just as unsettling, imbued with hints of magical realism that make us question the correlation between inner and outer worlds. ‘The idea of home – the image of it – rides that line between being deeply personal and completely universal,’ she says. ‘And that tension has always sat at the centre of my work. Home becomes a metaphor, a way of talking about the body in relation to community. It’s a space where we can navigate how the world gets internalised. To me, home is like an echo of the body in the place where it meets the world. It’s one of the rare metaphors that allows you to speak about the intimate and the political at the same time. I’m not just drawing the walls of a house, I’m drawing boundaries. And the emotion of the figure inside that space determines whether those boundaries feel like safety or intrusion. That’s something we all instinctively understand.

‘So I’ll draw a figure in the kitchen and talk about hunger, or desire, or class, or all three at once. Or a bath that speaks to identity, or shame, or becoming. A window might hold longing, or fear. The symbols of home root so deeply into human experience that they become a gateway to what’s essential. They give us a language to talk about what matters most. And when the world is fracturing, when homes no longer feel safe, we have to lean harder into that metaphor. We have to keep speaking about what threatens that safety, and keep imagining new ways to protect each other. The meaning behind home becomes not just a subject, but a form of shared responsibility.’

Haircut, 2024, by Henni Alftan

(Image credit: Courtesy of the artist and Spruth Magers)

The Butterfly Net, 2025, by Koak

(Image credit: Photography: courtesy of the artist and Union Pacific)

The meaning and the medium of home continue to grow. Juno Calypso’s photographs take the building blocks of a soft and feminine home – pink, soft furnishings, a pretty dress –and interrupt them with jarring symbols of consumerism or oppressive beauty rituals. For Do Ho Suh (showing at Tate Modern until 19 October 2025), the very fabric of home life becomes reconsidered in his immersive, large-scale installations that are a literal interpretation of our safe spaces. ‘I think in many ways, and for a lot of people who have moved around a lot, home is everywhere and nowhere,’ he says. ‘Increasingly I don’t really think temporally with these questions – so instead of “when” does a place become home, it’s perhaps more “how” or “what” is home? My idea of my Korean “home” only really emerged when I had left the country. Did it even exist before then? I was not aware of it – in emotional and phenomenological terms – when I was still in Korea.’

In the ephemeral forms of his fabric structures, the concept of home is lightweight, yet clearly defined. ‘The fabric has always been a conceptual choice. I started using it because I was exploring different ways of measuring the spaces I found myself within. The key element of the fabric is that it’s transportable – you can pack an entire house into a suitcase and carry it around with you. That’s one of the most important things for me. When I made the first translucent piece, of my childhood home, I travelled with it in my luggage from Seoul to Los Angeles, literally carrying that impression of space with me. I’ve always thought about architecture as clothing, clothing as architecture. Clothing is the smallest, most intimate inhabitable space that we can carry. Architecture is an expansion of that.’

Do Ho Suh’s ephemeral structures

(Image credit: Courtesy of Do Ho Suh and gallery)

The diaphanous nature of the fabric works on different levels, seen in its installation space. ‘I like that you can see the museum architecture through the walls. But also crucially that you can see the viewer moving through the work. The fabric architecture is activated by the viewer. It’s why it’s essential for me that the floor-based structures can be entered. They’re porous and, I hope, communicate a certain level of flexibility around notions of memory and location, as well as troubling the museum with domestic interlopers.’

This article appears in the October 2025 Issue of Wallpaper*, available in print on newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today