For me, art has never just been about creating something beautiful, it’s always been tied to family, to culture and to a sense of belonging. I come from four generations of artists from the Utopia region in the Northern Territory, with our family’s legacy starting back in the 1980s through my great-grandmother, Minnie Pwerle, my grandmother, Barbara Weir, and my great-great aunt, Emily Kame Kngwarreye.

Growing up surrounded by their paintings, stories and deep connection to Country shaped me in ways I didn’t even realise at the time. Art wasn’t just something we did, it was something we lived. Every painting carried knowledge, stories and a responsibility to keep that connection alive.

As I’ve grown into my own practice I’ve seen how much Aboriginal art has evolved. What once felt hidden away or undervalued is now being shown in leading galleries, auction houses and luxury collaborations worldwide. There’s a growing respect for Aboriginal art as fine art in its own right – complex, powerful and deserving of space on the global stage.

With that, more Aboriginal artists are reclaiming control over their stories and place. The original symbols that are used to tell our stories are still present in Aboriginal art today. These symbols have been passed down through generations, carrying meaning about Country, ancestors and our dreamtime stories. In my own work, I honour these traditional symbols – tracklines, bush foods and sacred sites – while also bringing in my own perspective.

My paintings are inspired by an aerial view of my grandmother’s country, Atnwengerrp, almost like a talking map from the sky. They show the landscape, the song lines, and the knowledge embedded in that land. The meanings stay the same, but how we share them shifts with time, experience and new ways of seeing the world. Today I see so many Aboriginal artists pushing boundaries and blending the old with the new.

We’re seeing our art translated into fashion, architecture, digital spaces and large scale public works. That’s exciting to me! It’s not about leaving tradition behind, but rather carrying it forward into new spaces and making sure our ancestors’ stories are seen and heard in places they’ve never been shared before. My journey with art really began when I was a toddler, sitting beside my nannas as they painted.

I was only two years old, sitting beside my great-great aunt, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, with a cardboard box and a paintbrush, trying to copy her – always watching, always fascinated. I went on to spend a decade in the fashion world, but as I grew older, I deepened my knowledge and better understood what had been passed down to me. I felt a stronger pull back and responsibility to my culture.

The more I learnt, the more I realised that this wasn’t just something I loved; it was something I needed to do. Choosing to make art my path wasn’t just a career move, it was a way to honour my family, my culture and everything that’s been entrusted to me. [My great-grandmother’s] fearless expression has left a legacy that lives in me and many others. My gallery, Pwerle, is in honour of her.

First Nations Artists To Note

Minnie Pwerle

My great-grandmother, Minnie Pwerle (who I named my gallery after), painted with unstoppable energy. This work represents women’s ceremonial body-painting designs.

The energetic lines and bold marks express connection to Country, kinship and the passing down of cultural knowledge through generations.

Barbara Weir

My grandmother, Barbara Weir, is a powerful voice in contemporary Aboriginal art. Her work embodies both personal resilience and deep cultural memory. A member of The Stolen Generations, she overcame immense adversity to reconnect with her family, heritage and become a celebrated artist and community leader.

Her Grass Seed Dreaming paintings are mesmerising, delicate, layered compositions that honour the traditional practices of Aboriginal women who gathered native grass seeds for survival.

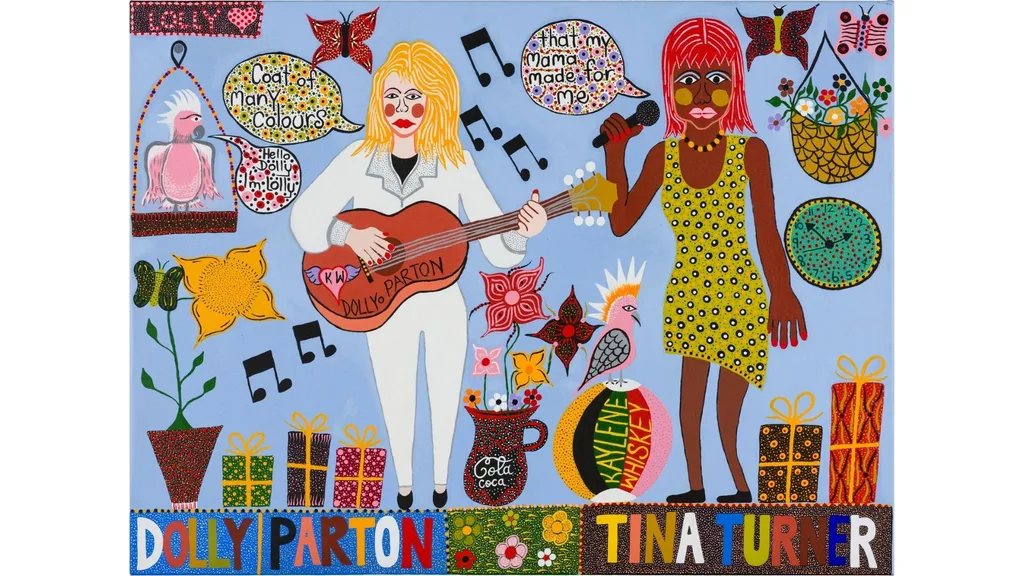

Kaylene Whiskey

Kaylene Whiskey’s vibrant, detailed paintings celebrate strong Aboriginal women, often blending pop culture icons such as Wonder Woman and Tina Turner with life in her remote desert community.

Her work playfully bridges traditional Anangu practices – such as bush tucker gathering and mingkulpa (tobacco plant) cultivation – with contemporary influences, reflecting two cultures and generations with humour and joy. The result is a bold and layered expression of modern Indigenous identity. Her work makes you smile and think.

Niah Mcleod

Niah McLeod’s gentle, spiritual works explore lineage and emotional healing. Her visual language carries a quiet intensity, honouring the strength of women and ancestral guidance.

This work tells the story of the generational wisdom of grandmothers, daughters and granddaughters, who together weave a tapestry of guidance, creating a path that recognises the past and

lights the way for those who will follow.

Glenda McCulloch & Cheryl Perez Of Cungelella Art

The Kalkatungu sisters infuse their works with colour, culture and kinship. Their art radiates pride and belonging, merging traditional stories with a refined, modern aesthetic. Together, they are redefining contemporary Aboriginal art while staying rooted in ancestral identity.

This work reflects our stories through intricate patterns, with each element holding meaning, making it visually striking and culturally significant.

Hannah Lange

A proud Wiradjuri woman, Hannah Lange paints with grace and thoughtfulness. Her art captures the spiritual elements of land and water with such softness, clarity and strength.

This work is inspired by the dance of water and stone, where the still water echoes the stories of our ancestors. The asymmetrical shapes are an art form in themselves and show off the beauty of Country.

Charmaine Pwerle

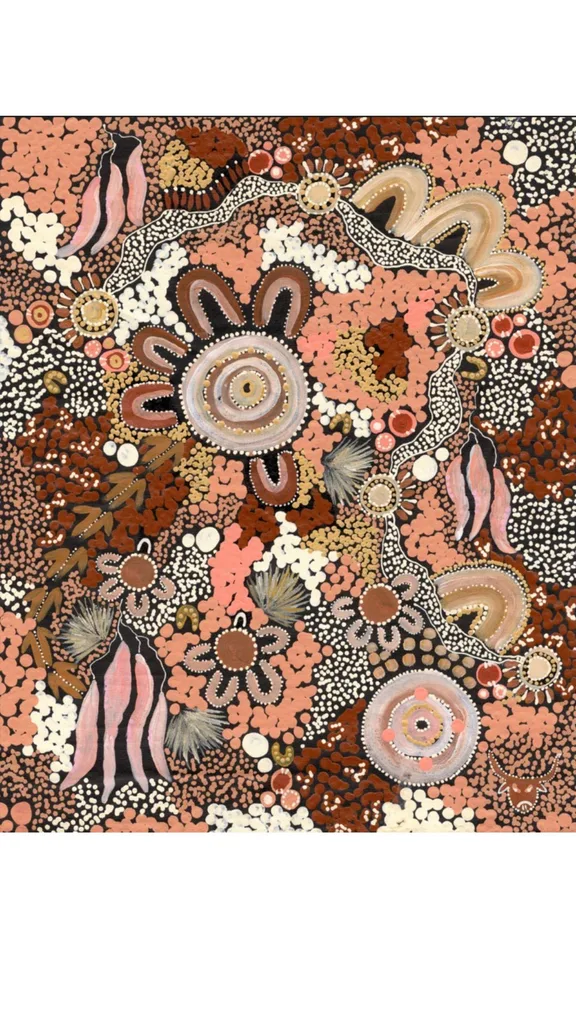

My aunty, Charmaine Pwerle, preserves a legacy of love, strength and cultural continuity through her brushstrokes and dot work. This painting (above) captures the final story passed down to her by her late mother, Barbara Weir, a deeply sacred narrative about traditional childbirth practices in the bush.

It honours the role of women as knowledge keepers, midwives and nurturers, revealing a time when birth was a ceremonial journey shared among women and passed from one generation to the next.

Lisa Khan

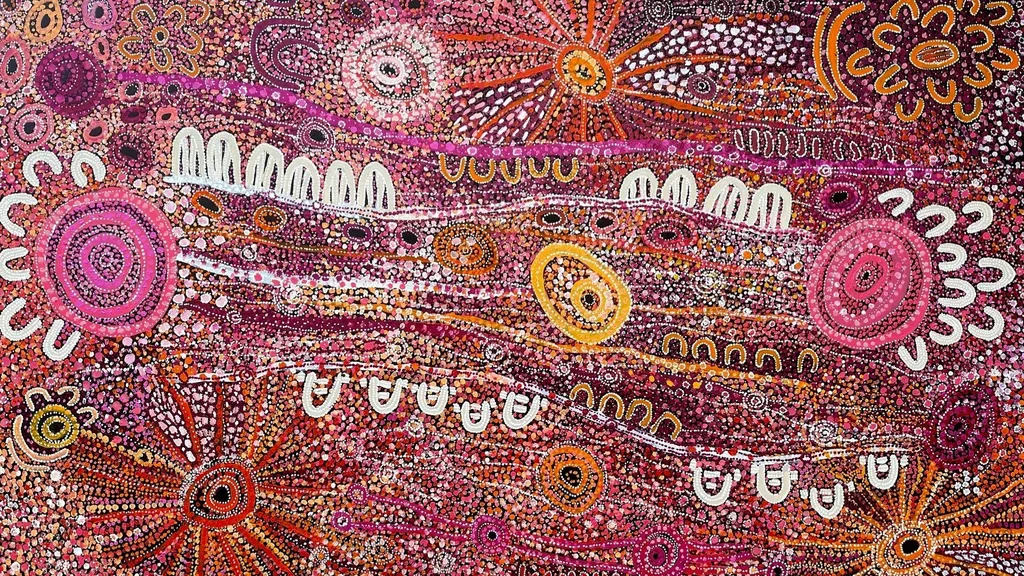

Lisa Khan’s art is grounded in the ancestral stories of her Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara heritage. Her work channels Country with bold, unapologetic power and cultural integrity. This painting is a visual embodiment of an important inma (a ceremonial song and dance) that connects people to Country.

Alison Munti Riley

Alison Munti Riley paints ancestral stories with care and reverence. Her work Kungka Kutjara honours the journey of two sisters travelling across the desert, echoing themes of kinship, obedience and longing. Her work moves me deeply because it speaks to the heart and spirit of lived experience.

Gloria Petyarre

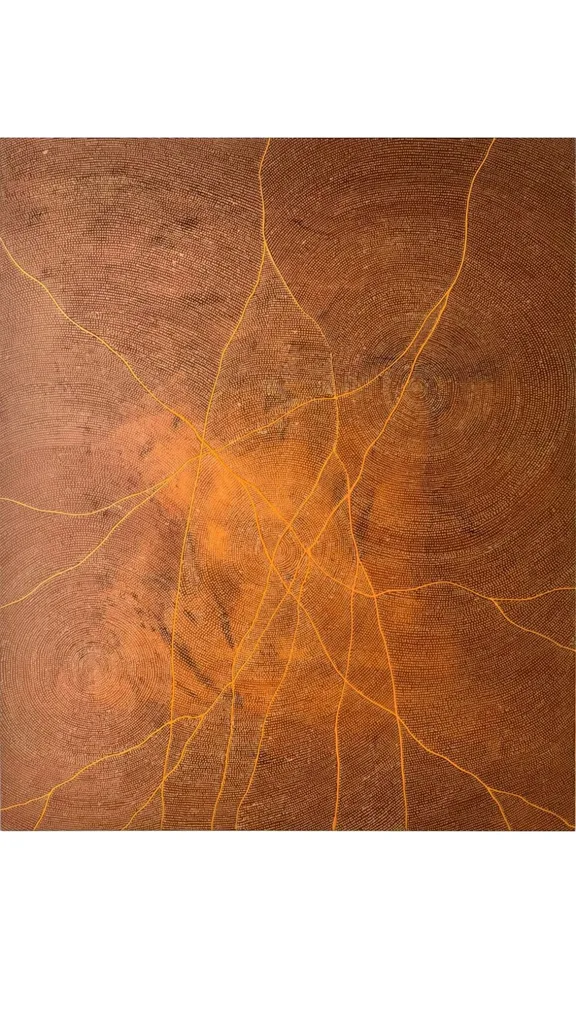

Gloria is my aunty and someone I deeply admired growing up. Being in her presence was healing, and her strength and spirit left a lasting impression on me. Her series Bush Medicine is among the most iconic in Aboriginal art, featuring swirling brushstrokes that capture the movement and energy of medicinal leaves gathered by Anmatyerre women.

This painting pays homage to the healing plants of her heritage, particularly the Kurrajong tree’s leaves, which are used in medicinal preparations. Her swirling brushstrokes reflect the movement of the leaves, the plant’s vitality, and its significance in Aboriginal culture.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye

Emily Kame Kngwarreye is my great-great aunt and one of Australia’s most important artists, who has redefined Aboriginal art on a global scale and continues to inspire me. As a toddler, I watched her paint in awe.

This work reflects Emily’s profound connection to her ancestral country, Alhalkere. Through vibrant colour fields and rhythmic dotting that illustrate the seasonal bloom of desert flora, she captures the spiritual and ecological cycles of the land.

Mary Dhapalany

Based in Arnhem Land, Mary Dhapalany is a renowned fibre artist who creates woven fish traps using naturally dyed pandanus.

Her work is functional and ceremonial, shaped by generations of women who understand how land, water and survival are intricately interwoven.