A recently opened exhibition of British art from the 1990s to today poses the question of whether a bad economy is good for art. The theory, say the organisers of Don’t Look Back at London’s Unit gallery, is that before the Cool Britannia surge of creativity, a recession spurred a subcultural movement that gave rise to phenomena such as Britpop and the Young British Artists.

Co-curator Sigrid Kirk draws parallels with today. “Downturns punish the market but open the space for artists, and [artists] are working together again today,” she says.

Whereas in the 1990s a subsequent economic boom helped fuel a post-recession spectacle, today, Kirk finds, the UK’s “fragile economy of high rents, student debt and post-Covid precarity” means “artists are developing different strategies.”

These include sharing resources, notably online, and more community-driven projects. She cites the Artist Support Pledge, an Instagram-based project that commits artists who sell to buy from their peers, and the Working Class Creatives Database (WCCD), conceived to support creatives who were not born into rich families.

Kirk and her fellow curator, Beth Greenacre, make the point at the entrance of their exhibition with a lively kiosk of artist-made merch including ceramics, clothes and posters, pulled together as a collaborative effort with Margate’s Quench Gallery. Individual items include twists on everyday objects, emitting a back-to-basics feel: there’s a bronze piece of toast turned into a medal by Grace Clifford, a WCCD member (“Bread Winner”, £600); framed, ceramic Post-it notes by Lindsey Mendick (£250); and T-shirts featuring a black bin bag (£50) by Gavin Turk, a reference to his bronzes from 25 years ago.

Elsewhere in the show, a revived taste for everyday reality stretches from mid-1990s photographs by Richard Billingham of his family in England’s Black Country to Clifford’s 2025 installation of empty plastic drinks bottles, called “My eternal chalice”.

Stories of culture rising from the ashes go back before the 1990s. Bank of America’s latest Art Market Update notes a shift in today’s collector habits, away from the “transactional, detached setting of an auction” towards more direct artist support that recalls the 1970s. This was, the report finds, “another period where traditional markets softened [and] artists and patrons created networks beyond the mainstream market to embrace community organisation and experimentation”.

Wars and political upheaval have long created the ingredients for artistic expression, as a means of communicating deep-seated and complex trauma. “Look how many great movements came after the second world war: abstract expressionism and then all the reactions against that,” says Marcelo Zimmler, founder of London’s Upsilon Gallery.

Showing at Art Basel Paris and its Cape Town base, Stevenson gallery this month shows a project based on artists working now and during the country’s “long decade” (1989-2004), encompassing the end and aftermath of the apartheid regime.

It was, says gallery partner Joost Bosland, “an incredible period of ferment, when the whole idea of what art could be in South Africa was up for grabs. Artists could walk through the doors that they had banged down.” These include Penny Siopis, whose reflections of a transforming world include exploring the traditions of the female nude, and the Cape Town-born Berni Searle, whose haunting photos address Black suffering.

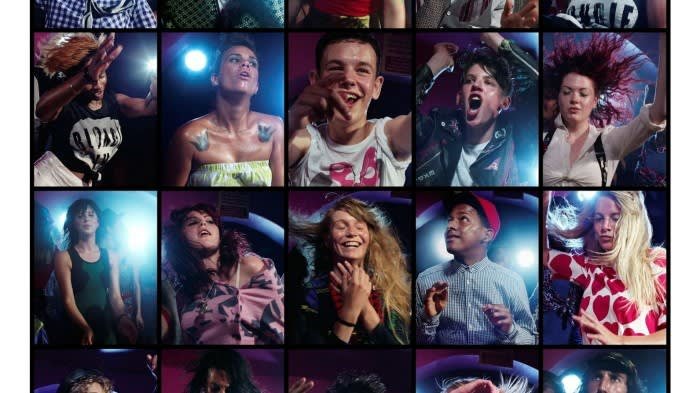

Today, there is more than a hint of nostalgia for the 1990s, including from artists who were not yet born then, Greenacre notes. Much of this is rooted in the surge of social media and, more recently, artificial intelligence, versus the seeming freedoms of the past. Greenacre cites a photomontage in her Unit show by Elaine Constantine, “Fuck Art Let’s Dance” (2008) — though this was in fact staged in a studio.

Photographs by the younger artist Bex Wade reach for places that social media and selfies have yet to dominate. The artist has moved from dancefloors to protests and now turns to Pride marches and the challenges of queer public life. “My work is about community, I’m not so interested when people become too aware of their own image,” they say.

There’s nostalgia too for a time before the transactional art market came to dominate artistic practice. “It’s like ‘things can only get better’ [an anthemic 1990s song adopted by Tony Blair’s Labour party] until they didn’t. People found that the market was, in fact, empty,” Greenacre says.

Some of the nostalgia is misplaced, finds Roman Kräussl, professor of finance at Bayes Business School and an art market specialist. For a start, he says, “the economy is not so bad at the moment, money is there, it is more that younger people aren’t as interested in art as it has previously been offered.” Plus, he notes, “we’ve seen a trend for a while now that once people get to their fifties, they start buying things that they couldn’t afford when they were younger, like tickets for the front row of an Oasis concert or art from that time.”

Unlike the 1990s, though, “it is looking impossible now to be a high-rolling banker, or even to afford business schools. It isn’t a time of crisis but there is a shake-up,” Kräussl says.

For the Unit show, Wade is proud to have work priced “accessibly” — digital prints in an edition of 20 are £245 each (and were popular takeaways from Friday’s opening), while signed, archival pigment prints on museum-quality paper are £1,450. “I want people to own the work, but not because of money, because I want them to feel something,” Wade says. And how do they live on that? “Badly,” though they add: “I will find a way. I’ve become a hustler.”

Love it or not, the surging and relentlessly transactional art market during better economic times enabled more artists to make a living. As Kirk says: “Artists once gathered because they could afford to play; today perhaps they are banding together to survive.” No one can promise that the art that comes out of this will be better but, she says, “history shows that downturns refresh the ecosystem.”

‘Don’t Look Back’ to October 25, unitlondon.com