Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Over the course of this year, whether I’m in my home city or travelling, I’ve made time to visit art galleries and museums, allowing myself a few hours to make my way through permanent collections. I walk, stop and look until I get tired. One of the most pleasurable and satisfying parts of this ongoing pastime is the moment I chance upon a work that arrests me, and that is also new to me. I always seem to have the same first reaction. Some version of “Wow, how have I never seen this before?” And then I get lost in all the thoughts that arise as I spend time with the exhibits. I’ve come across new works in the past several months that have made me laugh out loud, moved me, enraged me, or made me reflect more on a particular segment of society or a certain phase of life.

As debates around the representation of art and human history in public museums grow ever more intense, I’ve found myself thinking about how an exhibit can speak to us on any number of levels, and why spaces where a wide variety of works, created by a diversity of artists on an endless range of themes, are invaluable. It underlines the importance of making such places accessible to wide swaths of society. It shouldn’t surprise anyone reading this column to hear that I believe art can deeply affect how we consider the way we live and the way we see and understand one another’s experiences and histories.

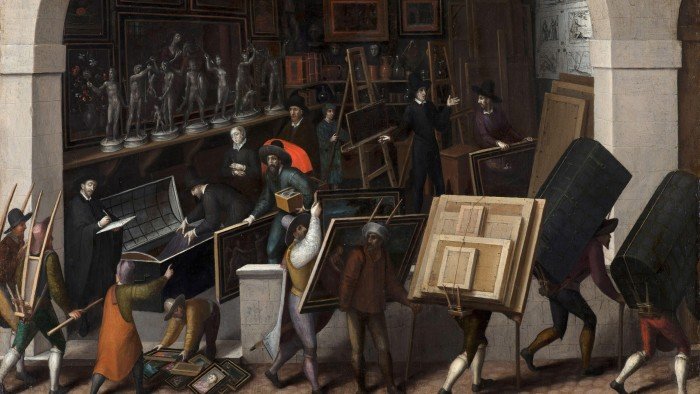

“The Confiscation of the Contents of an Art Dealer’s Gallery” is a work by François Bunel the Younger, a court painter for King Henry IV of France. Located at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the 1590 painting depicts several men carrying works of art and chests, presumably full of artefacts. There are paintings on the walls and sculptures, books and pottery on the shelves. At the back of the room we see a man, dressed in black with an uncertain expression on his face, gesturing to another person who is removing one of the works. In the left foreground a man in a black cloak stands close to a large open chest, and documents items. There is only one woman in the painting. She stands in front of the figure carrying an object covered by a red cloth. Her hands are crossed on her abdomen and she has a look of dismay on her face. We don’t know who has ordered the confiscation or why. It could be about a debt or because someone decided that these particular works should not be viewed publicly.

This painting reminded me that throughout history people have recognised the power of art, and figures in authority have felt threatened by certain works that pose a challenge to their ideologies. It has a severe feel to it, with the sharp angular lines of the canvases and easels, and the lean human bodies, elongated face shapes and pointed jawlines and beards. The people in the painting generally look similar. It is suggestive to me of the idea that deciding which art to confiscate is clear cut, that whoever orchestrated this event understands the world in an austere and somewhat unrealistically defined sense of black and white, right and wrong, without diversity of form and content. A world in which art is confiscated does not seem to be a world that has any room for an expansive and open imagination.

Titus Kaphar is a contemporary American artist and filmmaker. Much of his work explores the narrative gaps in history, highlighting ways that ideas and representations of the past remain relevant to how we comprehend present-day realities. He is also the co-founder of NXTHVN, a national arts initiative focused on mentorship, career advisory and educational programming for the next generation of artists.

Kaphar’s 2017 work “Shifting the Gaze” is based on the 1640s painting “Family Group in a Landscape” by the Dutch artist Frans Hals. Kaphar’s painting was completed during a TED talk titled “Can Art Amend History?” that he gave in 2017 about the importance of what we see in art and how we are taught art history. I highly recommend watching his talk. Kaphar shares a poignant story of taking his two young sons to the American Museum of Natural History in New York. At the entrance to the museum is a sculpture of Theodore Roosevelt sitting on a horse, with a Native American man and an African man walking beside him. As Kaphar and his boys approached the sculpture, one of his sons asked why Roosevelt gets to ride the horse and the other two men have to walk? Kaphar then explains to the audience how he understood that to be a question loaded with deeper questions about justice.

On stage, Kaphar goes on to unveil his own painted version of the Hals painting of the Dutch family posing in front of a large tree along a short expanse of countryside: a mother, a father, a son and a daughter, and a young Black boy understood to be the family’s servant. He discusses his understanding of painting as a visual language, pointing out what certain aspects of the Hals painting mean, and he uses white paint and linseed oil on his reproduction to partially paint over all the figures except the Black boy. What Kaphar is doing is inviting the audience to consider what they see in the painting, and whose stories don’t get told. It is a way of returning to his son’s question. An important aspect of Kaphar’s painting, which is now held at the Brooklyn Museum, is that he mixes linseed oil with the paint, and he explains that doing so will allow the underlying images to come back into partial view at some point in the future. So he is not erasing history or characters. He is trying to tell fuller stories.

People encountering this work for the first time are likely to have mixed emotions and immediate interpretations of its meaning. These initial reactions might lead a viewer to explore the story behind this painting and to learn more about how art can be a tool used to inspire a better understanding of how the past histories of others affect all our histories.

Contemporary German photographer Thomas Struth has been using his camera as both an artistic and investigative tool, exploring human nature, technology, public spaces and the natural world for close to five decades. “Louvre 2, Paris, 1989” is a Struth photograph of a group of elementary school children sitting together on the floor at the Louvre looking at works of art with their teacher. The grand room with vaulted ceilings and large historical paintings contrasts strikingly with the cluster of small bodies packed tightly together on the expanse of gleaming wood flooring. This composition creates an evocative sense of the intersection between history and contemporary times. Depending on what is available for us to see, the context in which things are shown and how we consider and interpret art, it is fascinating to think about what can be transferred in this sort of meeting. I love to think about the fact that the children in this photograph, taken in 1989, would now be 36 years older. Did this moment or museum visit affect any of them in any lasting way? Did art become an important part of any of their lives? Do any of them have a deeper recognition of the power of art to alter how we consider the world and our lives?

That same year, Struth began what is now known as the “Museum Photograph” series, in which he shot unstaged scenes of people engaging with art in museums across the world. One of the motivations behind the series was Struth’s interest in what it was that drew museum visitors to certain works of art, including religious and historical paintings. A question he asked himself at the time of his museum visits was: “What can you valuably take from pictures from the past, which might be a catalyst for interesting or productive ideas for the future?” I think this remains an invaluable question for all of us, and access to art that covers a range of themes from across cultures and time periods is essential for generating productive ideas for the future. Our shared humanity includes a collective shared history that can help inform how we create our future.

Email Enuma at enuma.okoro@ft.com

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning