At the end of the 1980s, a young woman purchased a slightly damaged print by the 19th century painter and printmaker Raja Ravi Varma for Rs 500. “I remember saying ‘this is a very beautiful image’,” she recalled later. “I’d never seen anything like it… I felt like looking out for more.” Given Ravi Varma’s status as a pioneer of mass produced imagery in India, it was a fitting introduction. In the following decades, Delhi-based Priya Paul – chairperson of Apeejay Surrendra Park Hotels – amassed one of the most significant collections of popular visual artefacts in the South Asian subcontinent.

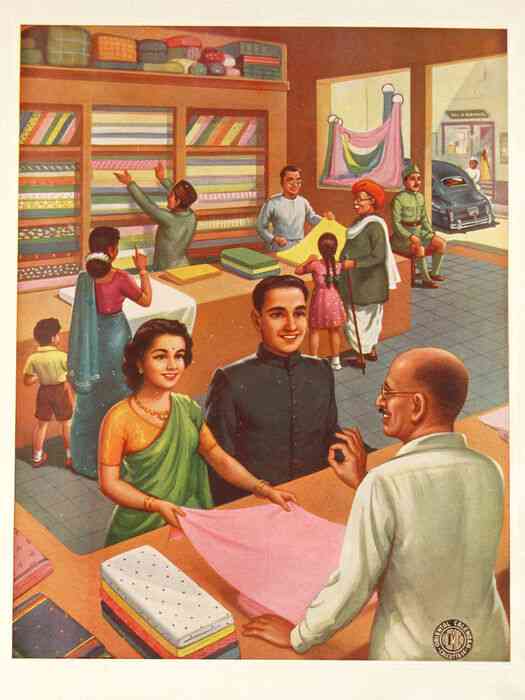

Building on this foundation, a transnational network of collectors and scholars called Tasveer Ghar launched an equally vital endeavour in 2008: to digitise the vast collection and make it freely accessible to the public. Hosted at the Heidelberg University’s heidICON image database, the Priya Paul Collection of Popular Art “contains over 4,200 images of Indian popular culture from the late 19th and early 20th century. A large part of the collection consists of old posters, calendars, postcards, commercial advertisements, textile labels [commercial labels that were glued onto parcels of textiles imported from Britain or made in India] and cinema posters…Sometimes they reflect an interesting blend of east and west: Asian subjects illustrated in western styles and vice versa for Indian or European markets.”

Where did Paul find these artefacts initially? “Delhi at that time was full…of little dealers and musty little antique shops,” she elaborated in an interview. “I’d see these pieces and think, oh my God, are they all on paper? I could see that they were deteriorating. So I really looked at it from that point of view, that is it going to last?” She soon found herself travelling beyond Delhi, often to Rajasthan, where the drier climate had helped preserve a greater number of visual materials. “I found a lot more works there that hadn’t deteriorated.”

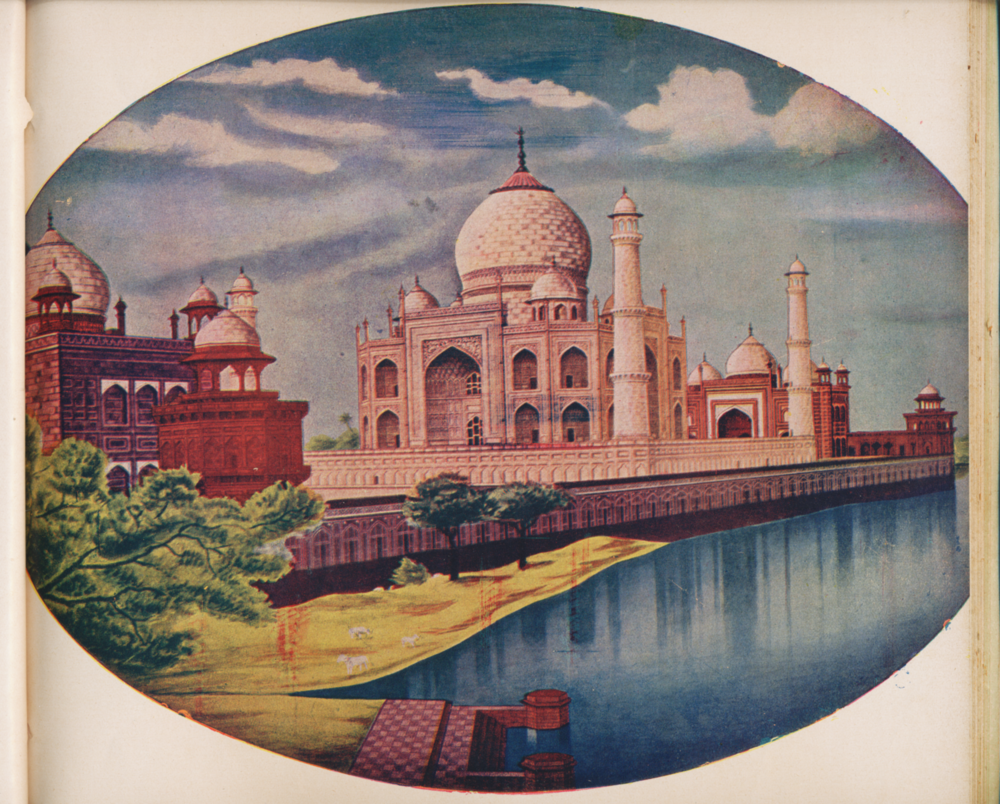

The heidICON database – available in both German and English – appears as a jewel-toned grid of thumbnails featuring retro images. At first trawl, Krishna plays the flute next to old Bollywood star Helen, Vivekananda glances over at the tea commercial in the next tile and the Taj Mahal glows radiant aside a map of India. A second dive yields an eclectic flotsam of late colonial and newly independent India’s commercial and social miscellany: textile labels, beauty soap ads, religious imagery, movie memorabilia and postcards with sublime landscapes, to name just a few categories. It is both sortable by filters such as object type, artist or author, decade, place of creation and theme, as well as searchable by keyword, should a user be seeking a specific article amongst the thousands in the repository.

During the 20-year period between the first Ravi Varma acquisition and Tasveer Ghar’s digitisation, the collection expanded considerably, driven by a curiosity that soon developed into a sustained passion. “It started with Varma,” said Paul. “I’d see a Ravi Varma matchbox label, then on a postcard…and discovered more about him and his work through that.” Eventually, her interest widened beyond Ravi Varma to ephemera in general. “What really fascinated me was the advertising part of it. As someone in business, it was interesting to see how visual culture was used to advertise – thread, cotton bales, cough syrup, beer…things like that. I started getting interested in how our culture and Western culture interacted – what was coming from there and what was going from here. The clash, the intermingling, the borrowing….That fascinates me.”

Archaeological excavation

The scope and depth of Paul’s mammoth effort became apparent when, in 2008, Tasveer Ghar – comprising filmmaker-researcher Yousuf Saeed along with cultural historian Sumathi Ramaswamy and visual and media anthropologist Christiane Brosius – took on the formidable task of cataloguing and publishing it. Recalling his first visit to Paul’s Delhi home, Saeed remembers the collection being in an upper storey room: “When I entered, it was not in very good shape; the material was lying around, there was a lot of dust and it was not classified. She hadn’t really found anybody to look after it.”

In an essay on Tasveer Ghar’s website, Saeed describes the experience as a kind of archaeological excavation: “[E]ach image needed careful handling, cleaning, assessment, scanning, digital photography, classification, and detailed annotation. It took more than 3 months to physically handle and scan the images into raw digital data…Each day, as we opened new drawers and shelves, or uncovered piles of framed posters and calendars, we found new surprises.”

To make these surprises available to the wider public, Tasveer Ghar also commissioned essays by the leading scholars of South Asian art. These articles not only help contextualise the images but also develop a taxonomy – by subject, genre, format, iconography and theme. In Consumption and Identity: Imagining ‘Everyday Life’ Through Popular Visual Culture, art historian Sandria Freitag maps the Priya Paul collection in terms of its “moments of production”, from the textile labels that naturalised imperial imports in the early 20th century to the commercial art of the 1930s in which the swadeshi spirit was incarnated as devis, grahanis and Bharat Mata to Nehruviana valorising progressive visions of modern technology and post-industrial rurality.

Other essays explore recurring visual tropes in the archive. Some trace the articulation of religious and nationalist iconographies (often co-constitutively), while others examine the depiction of gender, or alternative cinematic histories and even the depiction of landscapes and built heritage. In Artful Mapping in Bazaar India, Sumathi Ramaswamy highlights a unique print of Vishnu as Varaha the Boar, in his traditional attitude as the rescuer of Earth, except the young woman traditionally representing Earth is replaced by a gridded sphere: “Rather than ‘science’ triumphing over ‘religion,’ there is an easy co-existence as divine body and geo-body rest side by side.”

Reflecting on gendered representations, Abigail McGowan’s Modernity at Home looks at calendars and ads to unpack the allure of modernity for the late colonial “new woman” housewife. Through images of women drinking tea, talking on the phone, listening to the radio and even just sitting by themselves, they are offered the fantasy of a clean, orderly home in which she can partake of leisure rather than labour, and autonomy rather than servitude. Meanwhile, men get attention from Tarini Bedi in Wheeled Masculinity, wherein she regards representations of wheeled objects, such as automobiles, charkhas and chariots, as masculine signifiers: “[T]hey mark men’s relations with themselves, with their public aspirations and their more intimate sensory lives, with women, and with other men and other species.”

Glamour illuminates Paul’s collection in the form of beauty soap ads and movie memorabilia. Sabeena Gadihoke in her article Selling Soap and Stardom: The Story of Lux dissects an ad for Wright’s Coal Tar soap that places a traditional Indian housewife inside a modern bathroom. However, on closer scrutiny, “we see a tension: the woman’s figure is not complete and she seems superimposed against another, perhaps even alien space” – an uneasy consumer of modernity, caught between two worlds. Moving away from everyday fantasies towards the otherworldly desires projected by cinema, Rosie Thomas in Still Magic: An Aladdin’s Cave of 1950s B-Movie Fantasy casts a glance at stills and ephemera from B-movies of the 1950s and ’60s. She locates photographic glimpses of Aladdin (1952) and Alif Laila (1953), part of a mid-1950s wave of Islamicate legend and historical Bombay films that “came in a double register…apparent cultural authenticity as a refusal of all things western, but…carrying the prestige and branding of the genre’s Hollywood successes and a fashionable Europeanism. The Orient it peddled was a hybrid of east and west…”

Marginalised materials

Range aside, the sheer volume of articles at the Priya Paul Collection of Popular Art urges one to wonder after its original archiving process in 2008. Saeed explains that the digitisation was carried out through a flatbed scanner and a digital camera. “The real challenge,” he writes, “came while photographing numerous large-sized framed images. Removing the framed glass and putting it back after photographing was not possible within our limited resources and time. But since the glass reflected back the ambient light into the camera, we had to invent an ingenious technique of blocking the reflection by hanging a large piece of black cloth between the artifact and the camera (the camera seeing the image through a small aperture in the middle of the cloth).” The second stage involved “the formatting and digital restoration of all files” – such as judicious colour correction of yellowed vintage paper – as well as metadata creation which, as the Heidelberg University website notes, took place over 15 edit-a-thons.

Saeed elaborated: “When we started in the late 2000s, these databases were not so advanced, but heidICON allowed us to include two types of metadata: technical (scanning details, format, resolution) and descriptive (what the image depicts and means).” Even now, Saeed stated, the metadata is incomplete: “If we find information, we keep adding it on the back end.” Paul too has kept adding to her collection in the years since the initial archiving, the expanded assemblage accessible on request. But Saeed estimates that more than half of the total collection was digitised in the original effort.

Creating a digital archive of hitherto-marginalised materials in the early days of the South Asian internet was ambitious but also appropriate. Arguing for open source databases in Archiving Popular Visual Culture in South Asia, Saeed praises digital platforms’ interactivity and flexibility, allowing the public to hone in on details, run specific searches, do comparative analyses and access the archive without requiring literacy. At a more ideological level, he frames them not just as repositories, but as public commons: “Since the source (and the consumers) of bazaar art and popular images is public, the archive also needed to work in the spirit of open access, not only in exhibiting but also in acquiring the material… It is in such cases that digital copying and online archiving helps make these artworks open access for everyone – and return them to the public, where they belong.”

Throughout the 20th century, while institutional collections privileged “high” fine art, mass-produced and mass-consumed or “popular” visual material were largely ignored. During the 1990s and 2000s in India, collecting such ephemera may have had analogues in mainstream hobbies like philately or numismatics, but the critical framework to study them was lacking. By the end of the 1990s, there was a definitive academic turn towards studying the production and consumption of images circulating “away from structured, formal viewing settings like the cinema and art gallery…in everyday life”, as visual culture theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff noted in his essay What is visual culture? (1998). In India, too, by the mid-2000s, art historians such as Jyotindra Jain, Patricia Uberoi, Kajri Jain and Christopher Pinney had begun to chart this terrain. Uberoi’s collection inaugurated Tasveer Ghar’s digital archiving project. And it was in Kajri Jain’s book Gods in the Bazaar (2007) that Paul’s credit drew the team’s attention to the latter’s collection.

Two decades after the Priya Paul Collection of Popular Art was made public, how might we understand its value not just as a resource for researchers but as a historiographic intervention? Paul herself is convinced of its importance: “My mother used to ask, ‘What is this junk you’re collecting?’ And I’d say, ‘One day I’ll start a museum.’ This stuff tells the story of our times, our history. From an art history point of view – you can see how styles change. From a communication perspective – you learn how messages were delivered. From a social history lens – you can talk about costumes, mores, societal change…” She paused, then added firmly: “If we didn’t preserve this, we’d be at a loss. People preserve miniatures and antiquities, but this stuff – the bazaar stuff – is trashed. It’s our cultural history. I’m glad to have had a little part in it – and to open it up for people who are interested.”

Freitag offers a glowing review from the perspective of precisely those interested in the collection for what it reveals about the history of the quotidian: “Not until the advent of the large and diverse Priya Paul collection of popular visual-culture artifacts, however, have those who study the Indian subcontinent gained a real sense of the full range of formats, themes, and changes over time afforded by this kind of evidence from the past….A measure of the value of the Priya Paul collection comes from our ability, now, to think in new ways about the everyday.”

Kamayani Sharma is an independent writer, researcher and podcaster based in New Delhi. This project was made possible under the Scroll x MMF Arts Writer Grant.