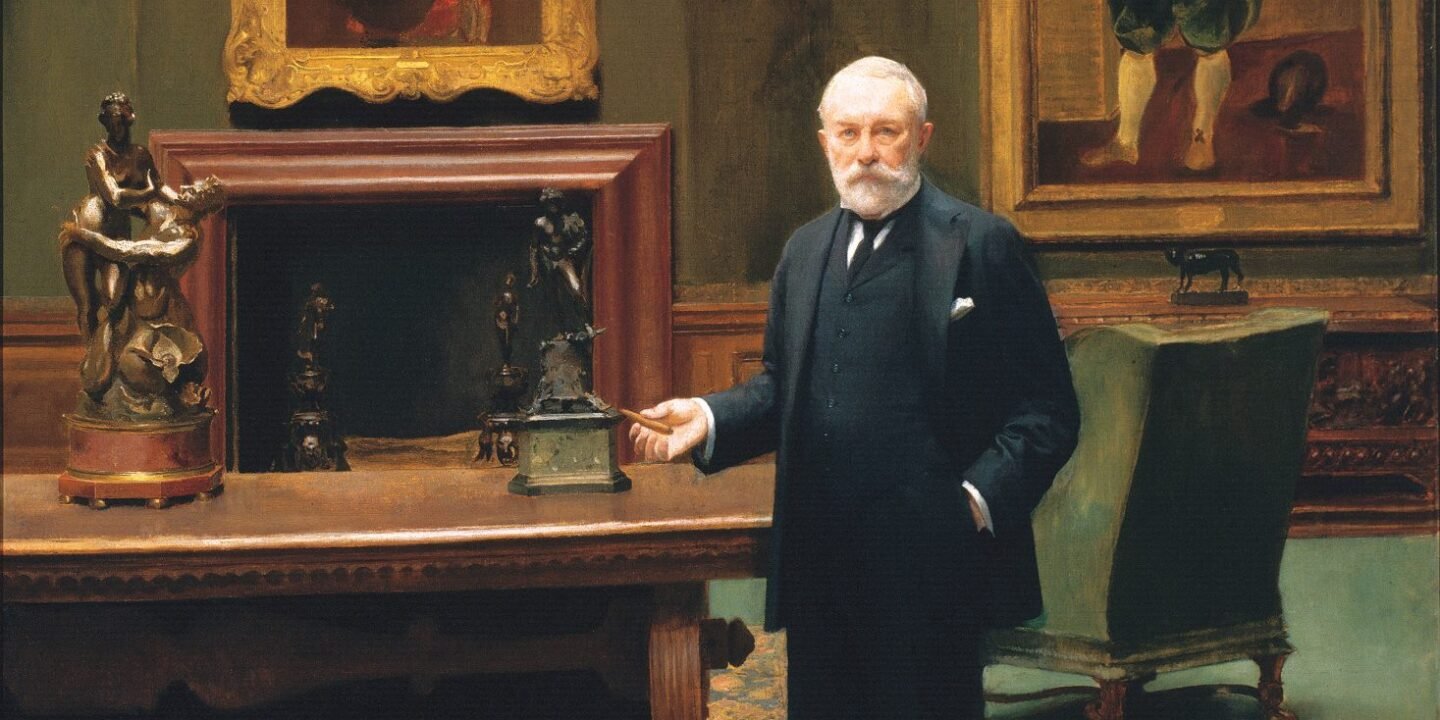

Art collecting in the modern age has always been both a personal pursuit and a mirror of social ambition—whether in Pittsburgh, Paris or London. Few figures embody this duality more vividly than Henry Clay Frick, whose collection transformed from modest beginnings in Pennsylvania into one of the world’s most admired ensembles. Today, the Frick Collection stands as both a monument to his vision and a living demonstration of taste, rivalry and legacy, offering lessons for collectors everywhere. These themes are examined in Ian Wardropper’s book The Fricks Collect: An American Family and the Evolution of Taste in the Gilded Age, which became the starting point during our recent conversation on Reading the Art World.

Origins: business acumen into cultural capital

Born in 1849 in West Overton, Pennsylvania, Frick rose from modest beginnings to become a titan of the coke industry, amassing his first million by the age of thirty. His reputation was contentious—after the Homestead Strike of 1892, he was called “the most hated man in America”—yet like his European contemporaries, the Rothschilds and Thyssens, he turned immense industrial wealth toward art, seeking refinement, prestige and permanence. What strikes me, and what I emphasize with clients, is that taste is not innate. It develops through exposure, education and resilience. Frick began with prints and Barbizon landscapes, the equivalent of a collector today starting with accessible works by contemporary artists. Through travel, friendships and mentorship by trusted dealers such as M. Knoedler & Co., he sharpened his eye until only Old Masters would suffice.

Wardropper described him in our conversation as “a thinking machine,” noting that Frick applied the same logic to collecting as to business: “Buying a work of art that he would [approach] as in buying a railroad company. He would analyze it, he would think about it. But in the end it has to be the combination of passion with the knowledge and the research that buttresses that.” Wardropper added that when Frick’s Pittsburgh home was full, “he began learning how to prune the collection… he could see one painting was better than another, and he began to develop his eye.”

Strategic collecting: from rivalry to refinement

Ambition alone does not make a great collection; structure does. Frick partnered with Charles Carstairs and the Knoedler firm to identify works of enduring value, pressing for provenance and scholarly opinion long before such practices were common. He studied his peers—J.P. Morgan, Isabella Stewart Gardner, Benjamin Altman, Andrew Mellon—not to imitate them but to sharpen his own path. When the Rembrandt Self-Portrait (1658) came onto the market in 1906, Morgan and the Metropolitan Museum hesitated, slowed by committees and divided scholarly opinion. Frick acted swiftly. Guided by Carstairs, he secured the work privately and decisively, outmaneuvering his rivals by combining speed, confidence and resources. That painting still hangs at the center of his collection, a symbol not only of discernment but of decisive judgment.

Competition was central to Frick’s refinement. Isabella Stewart Gardner, whose Boston museum opened in 1903, had already established a model of highly personal collecting. Benjamin Altman, the department store magnate, was assembling a formidable collection of Old Masters that would eventually go to the Met. Morgan, meanwhile, was buying voraciously across fields. Frick measured his progress against all of them, but rather than amassing broadly, he refined narrowly, concentrating on masterpieces of established reputation. Rivalry, approached with discipline, can be clarifying. It sharpens ambition and forces decisions not only about what to acquire but what to exclude. Frick’s genius lay in this editorial restraint.

Wardropper observed that “he becomes more selective, partly because he’s buying at the highest level of the market… These are front-page headlines in the New York Times. J.P. Morgan was the greatest collector of his day. But Morgan bought on block, en masse, big collections as well as among them some of the finest works in the world. That was not Frick’s approach. Frick was much more careful, studious, looked for the great work coming on the market, did his research and was willing to spend.”

Residences and display: architecture as strategy

Frick understood that collecting is inseparable from environment. His Pittsburgh home, Clayton, was carefully orchestrated to display Barbizon landscapes and decorative arts. In New York, he rented William H. Vanderbilt’s mansion, immersing himself in its built-in gallery, before commissioning his own Fifth Avenue residence from architect Thomas Hastings. That mansion was not merely a home but a private museum in embryo. The Picture Gallery displayed monumental Holbeins and Van Dycks, while smaller treasures like Vermeer’s Officer and Laughing Girl or Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert were placed with equal deliberation in more intimate rooms.

As Wardropper noted, Frick eventually realized that “to complete his vision for this house, he needed furnishings and decorative arts of the same level of quality. And he sought out to get it. In that he was aided by decorators.” The result was a holistic vision, where architecture, furniture and painting formed a unified environment—a lesson as relevant to today’s collectors as it was a century ago.

Legacy beyond the self

After Frick’s death in 1919, his daughter Helen Clay Frick became steward of the collection, expanding it and founding the Frick Art Reference Library, today a vital research center. Frick’s ambition was a museum “of the highest class.” Not every collector aspires to that. But every serious collector benefits from defining a legacy—whether that means building a foundation, donating to an institution or preserving works within a family. The clarity of that goal shapes acquisitions and ensures coherence for the future.

Wardropper emphasized that this commitment to legacy extended beyond display to education: “In reading Frick’s will, it’s clear that he also believes that his institution should provide, not only pleasure and solace, but also instruction and education to the public.” That ambition—pleasure balanced with instruction—remains one of the Frick’s defining qualities.

Enduring lessons

The Frick Collection endures because its founder combined ambition with discipline, curiosity with rigor. For collectors today, the lessons are universal:

- Educate your eye continuously. Exposure and study transform taste.

- Build trusted partnerships with experts. Advisors, scholars and conservators sharpen judgment.

- Refine without hesitation. Trade up, edit and pursue quality above all.

- Consider architecture and context. How art is displayed is as important as what is acquired.

- Define your legacy from the outset. Whether public or private, clarity shapes coherence.

Wardropper put it succinctly in our podcast conversation: “What I love about the Frick is it’s a very personal, very intimate space compared to most museums… an institution that encourages visitors to slow down and spend some time with a work of art.”

Art at its highest level is never about possession alone. As Frick’s story shows—and as I remind collectors—it is about stewardship, vision and creating a collection that will outlast its maker.

Learn more about The Frick Collection here, and The Fricks Collect here.

Megan Fox Kelly is an art advisor and the host of Reading the Art World, a live interview and podcast series with leading art world authors. The conversations explore timely subjects in the world of art, design, architecture, artists and the art market, and are an opportunity to engage further with the minds behind these insightful new publications. Listen to the podcast on Spotify and Apple.