Banco Santander announced on 21 January that it will manage 160 works from the Gelman Collection of 20th-century Mexican art. The result of a long-term agreement with the Zambrano family, which acquired the collection in 2023, this marks a new chapter for the renowned private collection of more than 300 works (including by Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera) that has largely been out of public view since 2008.

Pieces from the newly branded Gelman Santander Collection will make their debut this summer in the inaugural exhibition at Faro Santander, Fundación Banco Santander’s new venue in Cantabria, Spain. But the agreement is complex, as some of the works are National Artistic Monuments under Mexican law, restricting their mobility and mandating oversight by the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL).

The collection was started by Jacques Gelman, who was born in 1909 in St Petersburg, Russia. He arrived in Mexico in 1938 and became a central figure in the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema, producing films starring the celebrated actor Mario Moreno (known by the stage name Cantinflas). Jacques married fellow emigré Natasha Zahalka in 1941. The couple was close with several visual artists, including Kahlo and Rivera—both of whom painted portraits of Natasha—as well as Rufino Tamayo and Gunther Gerzso. Over time, the Gelmans acquired more than 90 works (later known as their “seed collection”) by artists including Francisco Toledo, David Alfaro Siqueiros, María Izquierdo and José Clemente Orozco.

“Formed as Modern Mexican art was unfolding, the collection reflects the ambitions of mid-20th-century collectors and the exceptional quality of Mexico’s Modern movements,” Ana Garduño, a researcher at INBAL, tells The Art Newspaper.

Diego Rivera’s Portrait of Natasha Gelman (1943) © 2026 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / VEGAP. Photo: Gerardo Suter

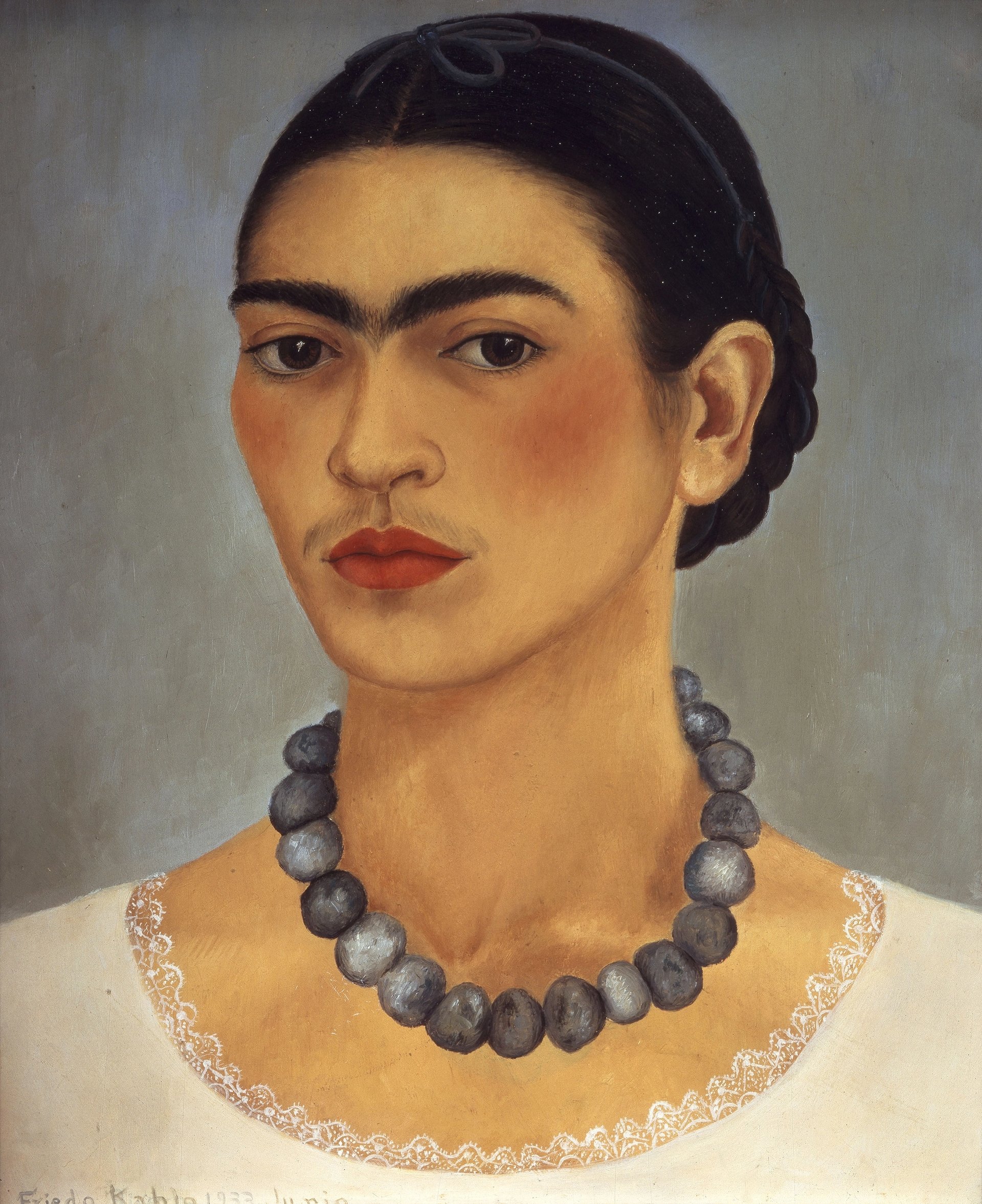

The collection’s prominence largely rests on its 18 Kahlo works—ten paintings, seven drawings and one print. “The collection changed over time, but what sparks interest in it is mainly Kahlo’s self-portraits,” says James Oles, a specialist in Modern Mexican art and professor at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. “There are many other relevant pieces, but these are the works—initially acquired by Jacques—that made it famous.”

Following Jacques’s death in 1986, Natasha continued acquiring art, advised by the American curator Robert R. Littman. When she died in 1998, Littman acted as executor of her will; he managed and expanded the collection through the Vergel Foundation, touring it internationally. (In 1998, the couple’s other collection of 81 European Modern works was bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. They also owned a pre-Hispanic collection.)

In 2008 the Gelman Collection largely receded from public view, reportedly amid inheritance disputes, after being shown at Centro Cultural Muros in Cuernavaca, Mexico. Scrutiny resurfaced in November 2024, when INBAL blocked the sale of a 1940 Izquierdo painting at Sotheby’s, citing national heritage laws.

In Mexico, the announcement of Santander’s deal has been largely met with scepticism. Many hoped the collection would remain in the country. (Natasha’s will allegedly notes that it should remain in Mexico and be shown at a private institution.) Furthermore, works by Izquierdo, Kahlo, Rivera, Siqueiros and Orozco are designated as Artistic Monuments under a 1972 Mexican law, entitling INBAL to supervise their conservation, location and reproduction. The law prohibits permanent export, allowing only regulated temporary loans.

David Alfaro Siqueiros’s Portrait of Natasha Gelman (1950) © 2026 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / VEGAP. Photo: Gerardo Suter

Legally, though, the works are able to remain in private hands. The Santander announcement revealed that the Monterrey-based Zambrano family, owners of the cement giant Cemex, had acquired the collection in 2023.

“Authorities can only verify that processes comply with existing laws,” Garduño says. “They cannot intervene decisively because, despite their importance—and even when some are Artistic Monuments—they are private property.”

Mexican authorities failed to act while it was still possible to do so and, over time, the collection’s value (particularly of Kahlo’s works) has increased significantly. “When Jacques was alive, Mexican authorities could have done something to acquire or negotiate the conditions on which the collection was handled or exhibited,” Oles says. “Sadly, now it’s too late.”

Fundación Santander holds that it verified the legal framework. “We worked closely with INBAL,” Borja Baselga, its director, told The Art Newspaper in a statement. “Both INBAL and the foundation share a priority: full compliance with customs regulations and the works’ conservation.”

Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Necklace (1933) © 2026 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / VEGAP. Photo: Gerardo Suter

In a statement, Mexico’s cultural ministry described the agreement as “private” but confirmed the collaboration: “INBAL will supervise the works’ shipment to Spain and, alongside the foundation, their conservation when they travel to exhibitions.” The ministry has also verified the collection’s “optimal conservation”, without providing details on the timeline for the temporary export. At a recent press conference, Faro Santander’s director, Daniel Vega, added that conservation considerations are key.

In June, nearly half of the 160 works managed by Santander—including the renowned “seed collection” and a photography collection featuring works by Guillermo Kahlo, Manuel Álvarez Bravo and Graciela Iturbide—will be shown at Faro Santander. “The loan request is extensive and still under review,” Vega said. “It is too early to specify where the collection, or parts of it, may be shown.” He described a potential presentation in Mexico as a “priority”.

“This remains a Mexican collection of Mexican art, which we will manage to share with the world,” Baselga said at the press conference.

For Garduño, the announcement prompts reflection. “This is an essential message for Mexican collectors who have built representative collections of national art,” she says. “What future do they want for their holdings?”