One of the invisible architects of 20th-century modern art, Peggy Guggenheim was not a curator but a collector, not a critic but an intuitive, not an academic but a woman burning with passion. She did not merely inherit her family’s fortune, she transformed it into a tool of resistance, supporting artists not only financially but emotionally, and at times, keeping them alive. Her story is not just one of art history, but also a narrative of the human soul.

Wealth, tragedy, emptiness

Peggy Guggenheim was born in New York in 1898. The Guggenheim family was one of the wealthiest and most influential in America during the industrial era. While male members of the family rose in business, her uncle Solomon R. Guggenheim began to redirect part of the family wealth into art, building a cultural legacy for future generations. Peggy, however, would carry and transform this legacy in an entirely different way.

At just 14, Peggy lost her father, Benjamin Guggenheim, in the Titanic disaster. This traumatic loss marked the first major rupture in her life. Benjamin valued his daughters’ education and filled their home with artworks. That aesthetic environment laid the emotional foundation for Peggy’s early connection with art.

What she lost with her father was not just a parent but her connection to the world she belonged to. She spent that winter almost entirely bedridden, retreating inward and finding solace in books. It was during this time that she encountered Chekhov, Oscar Wilde and Bernard Shaw, figures who shaped her intellectual identity. She never attended school regularly and completed her education at home with private tutors. These years of solitude became a transitional period that deepened her inner world.

At 21, she inherited her father’s fortune and in 1920, moved from New York to Paris. She would spend many years in the intellectual capitals of Europe – Paris, Berlin and London – rebuilding both herself and her relationship with art. Though she had no formal art education, her exceptional ability to see, sense and interpret would make her one of the most influential patrons of her time.

Her first serious encounter with art began when she worked at the Sunwise Turn bookstore in New York at age 20. But her true awakening came in the bohemian circles of Paris, where she was not only introduced to art but also to personal freedom. She became close to avant-garde artists, stepping onto the stage as both a collector and a marginal figure in a vibrant world.

Unlike her uncle Solomon, who later established a modern art museum bearing his name, Peggy chose a different path. More personal, more intuitive and at times, more rebellious. Unlike her sisters, she stood out with her sharp character, never afraid to shape her own destiny.

Life deepened by art

Paris in the 1920s was not merely a city; it was a mental explosion. The heartbeat of modernism pulsed there, breaking conventions in art and literature. James Joyce’s novels, Gertrude Stein’s salons, Ezra Pound’s poetry and Marcel Duchamp’s objects all coexisted in that same atmosphere. When Peggy arrived in 1921, she was in her early twenties. She had no academic background in art nor any dream of founding a museum. But her powers of observation, curiosity and courage drew her into the era’s most dynamic intellectual circles.

One of her most pivotal acquaintances was Marcel Duchamp. He became not just a friend but her aesthetic compass, introducing her to Dadaism, Surrealism and conceptual art. From him, she learned that art could be a form of resistance as much as it was an aesthetic expression. She began not just collecting art but understanding the way artists thought.

In 1922, she married American writer Laurence Vail. Their marriage was emotionally turbulent but intellectually stimulating. Vail was a known figure among Paris bohemians, surrounded by painters, writers and thinkers. They had two children: Michael and Pegeen. Pegeen became a painter but struggled to carry her mother’s legacy of vitality. Her life was marked by melancholy and she tragically took her own life in 1967 at the age of 41.

Peggy’s Paris years also freed her female identity. She rejected traditional roles as a “good wife” or “devoted mother.” She had lovers, made mistakes and was involved in scandals, but she always walked her own path. To her, artists were not just part of a collection, they were integral to her life. She formed friendships with them, supported them emotionally and financially, and often engaged in deep, complex relationships.

By the early 1930s, Peggy’s marriage had ended. She was now a single mother, but also a woman closer to her freedom. Her relationship with art deepened and her identity as a collector began to take form.

London, Guggenheim Jeune

In 1938, Peggy moved to London and opened her first gallery: “Guggenheim Jeune.” The name reflected both her famous surname and a desire for independence. The gallery hosted exhibitions for Jean Cocteau, Yves Tanguy, Henry Moore and Alexander Calder, and presented Kandinsky’s first solo show in the U.K. Guggenheim Jeune became a curatorial laboratory, where Peggy developed her intuition that modern art was not just to be displayed, but experienced. Duchamp continued to support her, playing a key role in her understanding of the avant-garde.

But war clouds were gathering over Europe. In 1939, she closed the gallery and returned to Paris. As the Nazis advanced, Peggy made a bold decision: “I will buy one work of art a day.” This was not mere collecting, it was cultural resistance. She acquired works by Picasso, Braque, Dalí, Ernst, Brancusi, Mondrian, Miró… all part of a mission to preserve a continent’s artistic legacy.

During this time, she began a passionate relationship with German surrealist Max Ernst. Declared a “degenerate artist” by the Nazis, Ernst was in grave danger. Peggy helped him escape to the U.S. and they married in 1941. Their union was short-lived, undone by her independent spirit and his emotional fragility. Still, their relationship exemplified her profound personal and intellectual bonds with artists.

New York: ‘Art of This Century’

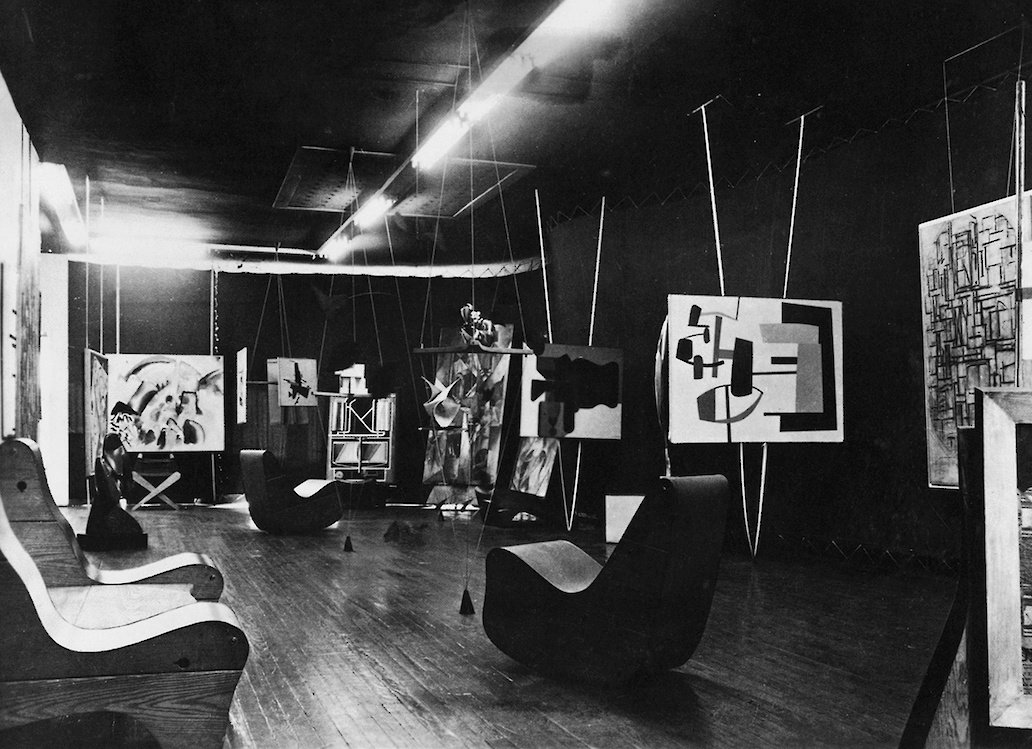

In 1942, Peggy launched her second major project, this time in New York: the “Art of This Century” gallery. Designed by architect Frederick Kiesler, it was no ordinary gallery. Its interior was theatrical, with wavy walls and dynamic lighting that invited the viewer into an immersive experience. Peggy wasn’t just showing art; she was transforming it into a visceral encounter.

“Art of This Century” became a bridge between European modernism and the rising American avant-garde. It was here that Peggy discovered a then-unknown artist: Jackson Pollock. She saw the raw emotional explosion in his chaotic canvases. She gave him a stipend, exhibited his work and encouraged his creative freedom. Many credited her as Pollock’s prophet rather than his manager.

Yet Peggy’s vision was not limited to male artists. She also championed women such as Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning and Frida Kahlo. In a time when female artists were often marginalized, Peggy used her gallery, publications and curatorial power to amplify their voices.

Venice: Construction of legacy

In 1947, Peggy returned to a devastated Europe, hoping to revive its art scene. A year later, she bought the “Palazzo Venier dei Leoni” on Venice’s Grand Canal. An unfinished 18th-century building, it was modest but striking. A fitting mirror of her tumultuous life.

Her participation in the 1948 Venice Biennale was historic, not only for her but also for American art. By exhibiting her collection, she introduced artists like Jackson Pollock to European audiences for the first time. Her courage helped American modernism gain global recognition.

The Palazzo became both her home and her museum. It was a living collection: visitors might find Peggy lounging with her dogs on the couch, surrounded by works of Kandinsky, Brancusi, Ernst and Picasso. For her, art wasn’t to be merely observed, it was to be lived with.

She remained there until her death, buried in the garden beside her beloved dogs. A quiet yet deeply meaningful peace.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Shortly before her death in 1979, Peggy transferred ownership of her collection and home to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. This ensured the preservation of her intuitively assembled collection within the institutional framework her family had built. Today, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection is considered one of the foundation’s three pillars, alongside its institutions in New York and Bilbao.

Final words: Life as manifesto

When Peggy Guggenheim died in 1979, she left behind more than a collection of modern masterpieces. She left the traces of a soul healed by art. Her life was a manifesto: a testament to the power of intuition over academia, to finding belonging in art and to the courage of stepping beyond comfort zones.

Today, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice is a living testament to her vision. It is more than a museum; it is a silent monument to a woman, a dream, a defiance. Every visitor there encounters not just art but Peggy’s resistance, her choices and her losses.

Yet, Peggy Guggenheim was more than a collector. She was a key figure in the acceptance and popularization of contemporary art. Often remembered as a solitary woman or criticized for her unconventional choices, today art historians recognize her intuitive brilliance with profound respect.

They see her greatest achievement as bringing art into the lives of the many, not just the elite. Her gallery designs encouraged emotional engagement, challenging the cold perception of modern art. In doing so, she helped build the first bridges between contemporary art and the general public.

Today, her curatorial vision remains a benchmark in the museum world. Female collectors and professionals follow in her footsteps. Peggy didn’t just add artworks to history; she added a perspective, a bravery, a method.

Note for today

Peggy’s story is not only a tale of art history but one of liberation. Her life stands as a symbol of the responsibilities that come with privilege and the courage of a solitary woman to change the world. Even now, women seeking their voices in male-dominated systems can look to her and know they are not alone.

Real legacy is not only about what you leave behind, but how you lived.

“I didn’t buy art, I saved it.” – Peggy Guggenheim