American billionaire investor Thomas S. Kaplan, CEO of the Electrum Group and a co-founder of Levantine Capital, is—together with his wife, Daphne Kaplan—a major collector and patron who is also deeply involved in philanthropy across the arts and wildlife conservation. In cultural spheres, he is probably best known for building one of the world’s most important private collections of Rembrandt and Dutch Golden Age works—a niche he’s been passionate about since childhood.

Over more than two decades, Kaplan and his wife have assembled a collection of more than 220 paintings and drawings—including 17 paintings by Rembrandt, the largest known private holding of the artist’s work, and the only Vermeer believed to remain in private hands. Known as the Leiden Collection, after Rembrandt’s birthplace, these works are not kept at home but instead function intentionally as a “lending library,” circulating through museum loans and exhibitions worldwide with the aim of making them accessible to a broad public.

In February, Kaplan will bridge two lifelong commitments—to art and animals—through the sale of the first Rembrandt he ever acquired, a rare drawing titled Young Lion Resting, in Sotheby’s Master Works on Paper from Five Centuries sale. Only six lion drawings by Rembrandt are known to exist, with the remaining five held by major public institutions: the British Museum (which owns two, believed to depict the same lion), the Louvre in Paris, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam. The sale of the work, which carries a high estimate of $20 million, will fund an endowment for Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization Kaplan co-founded in 2006.

He could have opted for a private sale, but he was acutely aware of the visibility bringing Young Lion Resting to Sotheby’s offered. “I wanted to raise awareness for Panthera—especially around the 20th anniversary—but also to make clear that this isn’t just a problem we’re talking about in the abstract,” he told Observer ahead of the sale. Panthera has advanced big cat conservation across dozens of countries, with tangible successes in protecting tigers, lions, snow leopards and jaguars. “The benefit is the visibility—and you can only hope that, when you find out who bought it, it’s someone you’d actually want to sit down and have dinner with,” he added with a smile.

Before landing in New York for the live sale on February 4, Young Lion Resting was exhibited in Paris, London, Abu Dhabi, Hong Kong and Riyadh.

Kaplan’s long-lasting love for Rembrandt

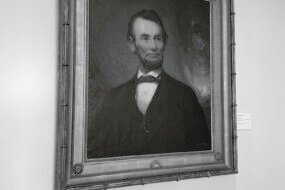

A formative visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art at just six years old inspired the collector’s appreciation for Dutch Golden Age artworks. “My mother took me to the Metropolitan Museum in New York to properly expose me to art, and the first place she brought me was the Rembrandt and Dutch Golden Age rooms,” he recalled. “I fell in love with Rembrandt from first contact. Every weekend after that, I asked her to take me back to see Rembrandt again.”

After countless visits, his mother decided to broaden his exposure and took him to the Museum of Modern Art—a shock of a different kind: “I remember being confronted with a big white canvas with a red line across it. I crossed my arms and said, ‘Mommy, take me back to Rembrandt.’”

And she did. While Kaplan does not remember the very first Rembrandt he encountered on that initial visit to the Met, he vividly recalls the one he saw after the traumatic visit to MoMA. “It was Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer. It had been acquired in the 1960s for a few million dollars, and I believe it was the most expensive painting ever sold at auction at the time,” he said. “Today, of course, it would be worth billions.”

No one in Kaplan’s family collected art, and for many years his passion remained a deep appreciation rather than an ambition to own. It expressed itself in repeated pilgrimages to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, particularly during his years studying in Europe. The idea that he might one day own one of these masterpieces never crossed his mind. It was his mother-in-law, the artist Mira Recanati, who suggested he consider it. “I told her, rather pompously, that I would never be a vulgar materialist,” he recalled. “One year later, I was buying, on average, a painting a week for five years.”

That shift in mindset resulted from a serendipitous chain of encounters. In 2003, during a summer trip to Croatia, Kaplan met Sir Norman Rosenthal, then head of the Royal Academy. “Over a casual conversation, he asked me what I would collect if I ever did, and I said Dutch Old Masters, particularly the Rembrandt school—though it never crossed my mind that I would actually own a Rembrandt. I assumed everything I loved was already in museums. He told me that wasn’t the case, and that conversation changed everything.”

A few months later, Rosenthal encountered a dealer in London with a painting by Gerrit Dou, Rembrandt’s pupil, and helped Kaplan acquire it as his first purchase. From there, he said, his collecting accelerated. “A few years later, I bought my first Rembrandt at Sotheby’s, and over the past two decades, we’ve managed to acquire about half of the Rembrandts still in private hands. We now own eighteen.”

Over time, Kaplan started to focus on Old Master drawings. Today, he owns two Rembrandt drawings, the most important of which is Young Lion Resting. “At the time, it was the most expensive work of art we had ever bought,” he explained, recalling how he visited the gallery with his family and returned home without speaking. When he was finally alone with Daphne, and asked what she thought, she said, “It’s Rembrandt, it’s a lion and it’s beautiful. If this isn’t for you, then who is it for?”

“I asked whether I should tell the dealer I was willing to negotiate,” Kaplan recounted. “She said, ‘I wouldn’t negotiate too hard. You will never see anything like this again.’ And she was completely right. Timing matters, and that drawing was going to be one of the most highly valued drawings ever. After that, she just said, ‘I’m going to make dinner.’”

Kaplan has always shared his collecting journey with Daphne, who was already a collector of 20th-century design. “She brought me into that world, and I brought her into Old Masters,” he quipped. “But I’ve definitely been responsible for spending much, much more money than she has.”

Kaplan’s interests soon expanded to include Italian design, particularly the Torinese school and the work of Carlo Mollino. That commitment culminated in a record-setting purchase: in June 2005, he paid $3,824,000 at Christie’s for a Mollino table from 1949, far exceeding its presale estimate and doubling the previous auction record for design furniture.

That purchase, he explained, caught the attention of Bruno Bischofberger, the legendary collector and longtime Warhol dealer, who invited him to Zurich to see his own Mollino collection. When asked to select a piece, Kaplan chose what he considers the most beautiful example of 20th-century design—a Mollino table with accompanying chairs. “I paid double what I had just paid at auction, because once people see what you’re willing to pay, they’re suddenly willing to offer you things.”

While Old Masters and 20th-century design are currently enjoying renewed market attention, the couple was never interested in trends. All collecting decisions were made as a unit, guided by instinct and conviction. While they worked with dealers and auction houses, they never relied on art advisers. “I know almost immediately—within 20 or 30 seconds—whether I wanted something. I went with what I liked. The choices were always very personal: the subject, the artist, the object itself,” he said.

A sale for wild cat conservation

During our conversation, which took place over Zoom, Kaplan used a photograph of a majestic Arabian leopard as his background and said that Panthera is currently leading a breeding and reintroduction program for the big cat in Saudi Arabia, where the species has gone extinct in the wild. Working at the request of the Saudi government, the initiative forms part of a broader environmental rehabilitation effort centered on AlUla, with the goal of restoring a fully functioning ecosystem before reintroducing the leopard at the top of the food chain. While full reintegration will take several years, early milestones have already been reached, including the birth of rare triplets in captivity—an important indicator of the program’s progress and long-term viability.

Active today in more than 35 countries and a global leader in wild cat conservation, Panthera works to protect 40 different species of wild cats. The organization focuses, of course, on the “big seven”—tigers, lions, jaguars, leopards, mountain lions, cheetahs and snow leopards—but also on 33 lesser-known species of small wild cats.

Protecting them also means safeguarding the broader landscapes and ecosystems they depend on. According to Kaplan, because wild cats sit at the very top of the food chain, an entire ecosystem must be in balance before they can survive in a given environment. “Cats are fundamental to ecosystems: if you think of an environment as a pyramid, at the base you have plants and smaller species. As you move upward, the umbrella species is the carnivore—or humans, of course—but in most ecosystems, that apex role is filled by big cats,” he explained, noting that if an ecosystem can support big cats, it means there is sufficient flora and fauna. “While we focus on cats, our work ultimately supports thousands of other species across the habitats and landscapes where we operate.”

Kaplan’s passion for wildlife also began early. Growing up in Florida, he was inspired by the iconic Florida panther—an early encounter sparked his dream of working in wild cat conservation and ultimately informed his decision to co-found Panthera with the late wildlife biologist Dr. Alan Rabinowitz, who shared his vision.

Multiple passions, one commitment

Kaplan describes himself as a case study in childhood imprinting: “I fell in love with cats, with Rembrandt, with history and with antiquities all at the same time, when I was six years old.” He managed to carry all of those passions into adulthood and make them central to his life. With Rembrandt, there is the Leiden Collection; with cats, Panthera; with history, his academic path through Oxford, where he earned his PhD. With antiquities, Kaplan became chairman of the International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage (ALIPH)—a Geneva-based foundation supporting concrete and sustainable initiatives to protect the richness and diversity of the world’s cultural heritage, with over 575 projects in 64 countries to date. “I’m passionate by nature; when I’m interested in something, I go all in, and when I’m not, I don’t spend time on it. I happen to have multiple passions,” he reflected.

What unites them all is a shared denominator: beauty. But focusing on beauty doesn’t necessarily mean pandering to it. One of the reasons Rembrandt stands, for Kaplan, as the most important painter of all time is precisely because he broke with classical conventions of beauty. “Before Rembrandt, beauty followed strict, idealized forms shaped largely by Italian and Spanish, church-influenced traditions. Rembrandt saw beauty differently,” he said. “He found beauty in what others considered ugly—in what was real. At the time, people thought that was vulgar.”

Rembrandt’s legacy, Kaplan argued further, lies in how he liberated generations of artists to follow. His influence runs through Goya, the Impressionists, Van Gogh—who was obsessed with him—all the way to Francis Bacon and contemporary art. “That’s why I call Rembrandt a universal artist, and why that idea became the theme of our first exhibition in Paris in 2017, when we revealed the collection publicly for the first time.”

Since then, selections from the Leiden Collection have been exhibited at the Louvre in Paris, in Beijing and Shanghai, in Moscow and St. Petersburg, at the Louvre Abu Dhabi and in Amsterdam. A dozen works are currently on view at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach in the first major U.S. presentation of the collection.

“I grew up in Florida, but more than that, I was impressed by what the museum’s director was doing. When he asked, I said yes. It turned out to be one of the most beautiful exhibitions we’ve ever done,” Kaplan said, noting that until the Leiden Collection arrived with 17 Rembrandts, the state had never exhibited a single painting by the artist. “You never know who you might reach. Not everyone can travel to Europe. And the way the exhibition has been installed—it’s dramatic, it’s beautiful—it allows people to encounter something, some true beauty, they otherwise never would.”

Looking to the future of the collection, Kaplan shared that while his children value art, they are not materially driven to own or sell it. He has encouraged them to make their own decisions rather than leaving them with the responsibility of interpreting his intentions later. For now, the long-term future of the collection remains an open question, with several possibilities under consideration.

In many ways, the Leiden Collection already operates like an independent entity—circulating through museums on loan and functioning much like a foundation. Formalizing that structure, however, presents its own challenges, particularly around governance. Although Kaplan remains open to different models, he emphasized that any framework, such as a foundation, would require clearly defined parameters to ensure the collection’s mission is preserved. What he made unequivocally clear is that the collection will not be sold at auction nor donated outright to a single institution: this is the only work that will come to auction, and only then because of its potential to amplify Panthera’s mission.

More art collector interviews