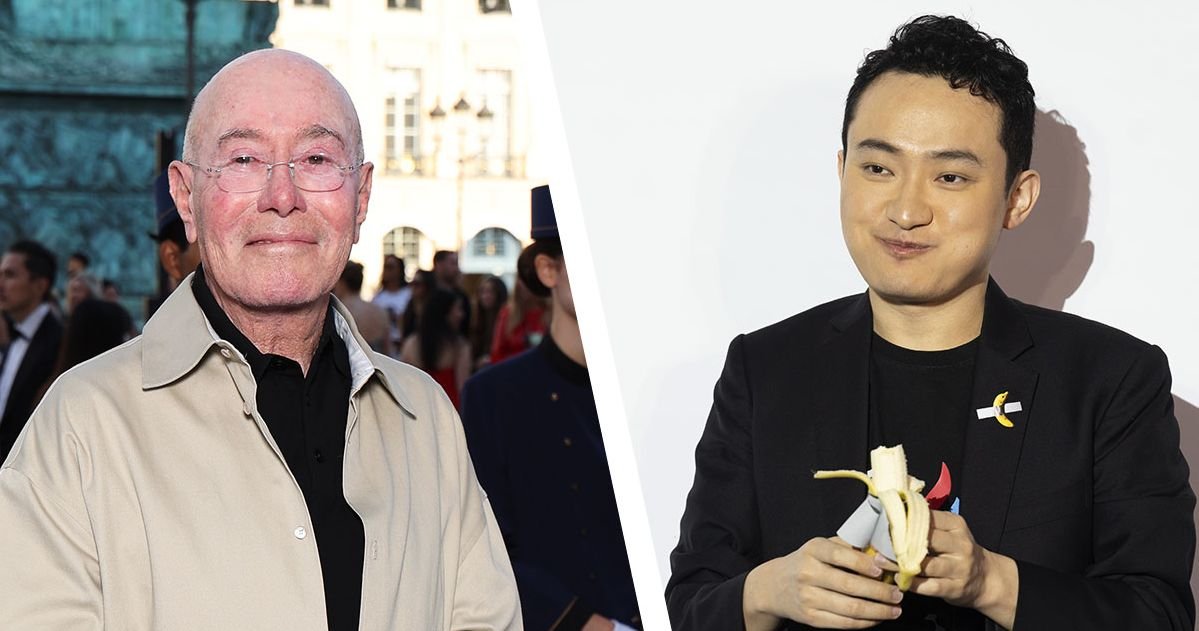

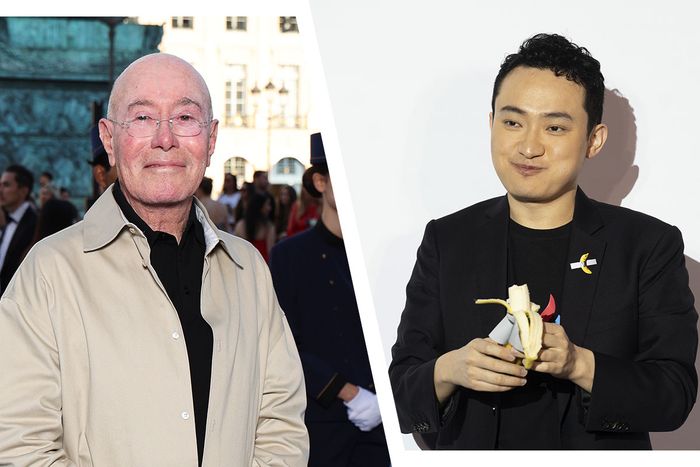

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photos: Getty Images (Pascal Le Segretain, Justin Chin/Bloomberg)

In late 2021, Sotheby’s held one of the highest-grossing auctions in its history. The star lot of the $922 million sale, featured on the catalogue’s cover, was Alberto Giacometti’s 1949 sculpture Le Nez, a skeletal bronze head with a long, thin nose, hanging from a cord in a large cubic cage. Two Sotheby’s representatives competed for the work on behalf of two anonymous clients, and the winning bid was placed by a Hong Kong specialist. The total price, including fees, was $78.4 million.

Buyers of such significant artworks are typically a secretive bunch, but this one outed himself, and the price he’d paid, immediately on Twitter: It was Justin Sun, the 34-year-old billionaire, born in China, and founder of the crypto platform Tron, who would, in November 2024, become known for buying and eating artist Maurizio Cattelan’s work Comedian—the banana duct-taped to a wall.

Now, three and a half years after the Sotheby’s auction, Sun is locked in a legal battle over Le Nez with 82-year-old David Geffen, the entertainment mogul and arts philanthropist. In January 2024, the work was sold to Geffen, seemingly on Sun’s behalf — Sun now says the sale was illegitimate. In February this year, he filed a lawsuit against Geffen, demanding the return of the sculpture or at least $80 million in damages. The Giacometti, he said, had in fact been stolen by his own art adviser, Sydney Xiong, via forgery, and sold without his approval.

This morning, Geffen countersued in Manhattan federal court, arguing that Sun was aware of the sale the whole time and that he concocted the story of fraud after the fact in a case of “seller’s remorse.” Geffen is asking the court to grant him free and clear title to the sculpture and to require Sun to pay him a sum equivalent to “all of the fees and other costs associated with this bogus lawsuit.” (A representative for Sun declined to comment.)

The fight between the two very different billionaires is emblematic of a growing culture clash in the art world, as the old guard faces off with collectors from the tech sector who tend to be less reverential toward the market’s norms. Nearly every move Sun has made has been antithetical to traditional art collecting. Until recently, he was known mainly for buying NFTs, and he once favorably compared an early NFT, EtherRocks, to Picasso’s Cubist innovations. Sun is also an admitted art-history dilettante: He didn’t know who Giacometti was until Xiong gave him a history lesson just before the sale. And, perhaps needless to say, he loves a publicity stunt. Cattelan’s banana, which he ate at a press conference, cost him $6.2 million. “It’s much better than other bananas,” he told the crowd.

Geffen, meanwhile, is a lion of the Manhattan patron class, whose name adorns a wing at MoMA, a building at LACMA, and a hall at Lincoln Center. Where Sun is a dabbler, Geffen is an established connoisseur. The curator Paul Schimmel once likened Geffen’s personal collection, estimated to be worth $2.3 billion, to a museum: “It is to postwar American art what the Frick Collection is to Old Master painting.”

Exactly what happened with Le Nez is unclear. In 2023, Sun decided to sell the sculpture, and Xiong set out looking for a buyer. (Giacometti’s métier — frail, thin figures, crushed by a world closing in on them — may not have suited the banana guy after all.) Geffen, who already owned the most expensive Giacometti ever sold, the $147 million Pointing Man, was a good place to start.

Sun knew of Xiong’s discussions with potential buyers but alleges that she went rogue and made the deal unilaterally, agreeing to sell the sculpture to Geffen in exchange for $10.5 million and — to make up the difference between this price and what Sun had paid for it — two unnamed paintings said to be worth tens of millions. Sun received a $10 million transfer to his crypto wallet in early 2024, but contends that he learned Le Nez had been sold later, only after it was already installed in Geffen’s New York apartment. He says he understood the transfer as merely a deposit establishing a collector’s serious interest in potentially buying the work.

“This is frivolous, and it’s a fraud on the court,” Geffen’s attorney, Tibor Nagy, said, speaking with me before filing the countersuit. In challenging Geffen, he said, Sun had “come up against someone who is a really bad draw for him. Geffen is not going to be cowed.”

Indeed, Geffen filed nearly 100 pages of counterclaims, some of which point to signs that Sun may have known about the transaction all along. It alleges that he had multiple “communications” with Xiong, including by phone, regarding possibly selling the two paintings he’d received from Geffen. The countersuit also accuses Sun of exchanging WhatsApp messages directly with two L.A. art dealers who were trying to sell the paintings on Sun’s behalf — these messages, in the words of the new complaint, were then “surreptitiously” deleted. According to Nagy, one of these art dealers has claimed that Sun planned in advance to “pressure Geffen” into returning Le Nez.

Sun, for his part, says that Xiong came to him to confess her double-crossing in December of last year. She laid out the alleged scheme in an affidavit: She’d had a friend pretend to be Sun’s attorney on emails with Geffen’s team, purposely withheld information from her boss, and forged his signature on multiple documents. “I sincerely now regret my involvement in this matter and have resolved to do what is required to make amends,” she wrote. If this is all true, Xiong’s motivation isn’t clear: The affidavit states that she forged the signatures because she was “under duress”—pressured by the L.A. dealers to finish the sale in a hurry. Sun claims, however, that Xiong had hoped to pocket $500,000 and give him only $10 million of the incoming money. Before the turn of the New Year, Sun’s attorneys informed Geffen of Xiong’s confession and declared that the deal had been “fraudulent.”

According to Sun’s complaint, there was also another problem with the Geffen arrangement. Sun had planned to donate Le Nez to his nonprofit foundation, APENFT, and the sale was in fact made by the foundation, of which Xiong was the director. But Sun says that he in fact never donated the work — a sale from APENFT was therefore invalid.

Geffen’s filing asserts that this makes little difference. (“Sun founded APENFT, dominates it, and controls it,” it reads. “It is his alter ego.”) The suit also paints a clownish portrait of the entrepreneur, portraying him as pompous, shameless, and untrustworthy. In 2021, Sun was briefly named Grenada’s ambassador to the World Trade Organization (something that happens to billionaires, apparently), after which one of his senior employees instructed staff, on Slack, to refer to Sun as “His Excellency.” His stint as a diplomat ended when the Securities and Exchange Commission opened a securities-fraud case against him, alleging that his companies had engaged in market manipulation. (His website and X handle still identify him as “H.E. Justin Sun.”) In February of this year, the SEC paused the case. Reuters reported at the time that Sun had recently funneled $75 million to the Trump family’s ailing crypto fund, World Financial Liberty.

Geffen’s countersuit also points out that Sun has been alleged to mistreat employees in the past, implying that Xiong may have been coerced into her confession. In 2023, he settled a lawsuit brought by two former Tron staffers who accused him of harassment and retaliation after they’d reported what they called “blatantly illegal, unethical, and unscrupulous business activities” at his company, including physically assaulting another employee.

As of Wednesday morning, how the dueling suits and competing claims would play out was uncertain. Nagy was sure the court would side with Geffen, if it went that far. “There’s just no doubt Geffen is so overwhelmingly right and Sun so overwhelmingly wrong,” he said. “I think he’s going to either drop it or feel the consequences pretty quickly.”

Nagy remarked that Sun had effectively written this scandal into the ledger of Giacometti’s sculpture. “The fact that Justin has done this,” he said, “puts that in the history of this work.” The art market at its highest levels is built on relationships and respectability: Even if this is all swiftly resolved, that any of it took place could be off-putting to future collectors — a kind of psychological stain on the work.

Meanwhile, the narrow nose of Giacometti’s sculpture extends beyond its metal frame, as long as the branch of a tree. It looks quite a bit like Pinocchio’s, growing between the bars of his cage. If there’s a liar in this story, who it is remains to be seen.