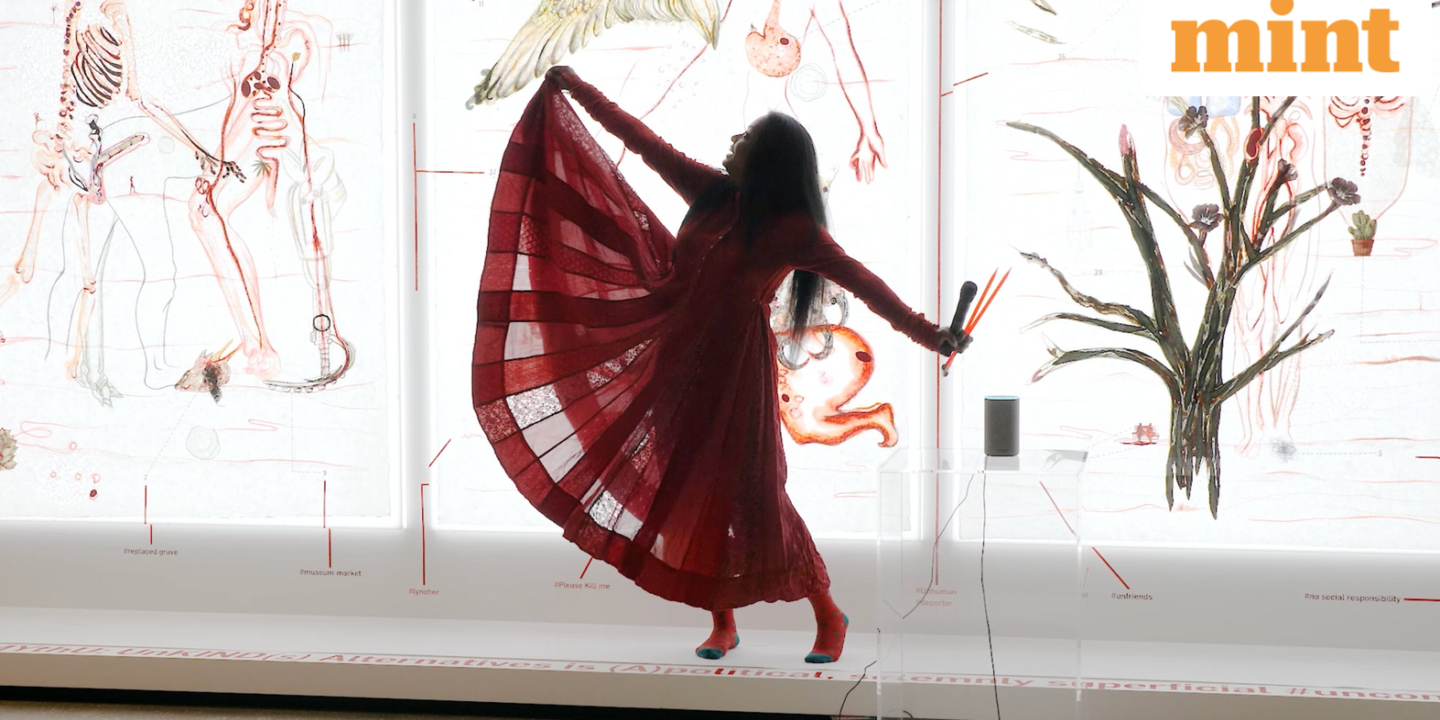

Can there be a price affixed to a form, which is temporal and created in response to the viewer? Being a work of art, a performance piece too is subject to the vagaries of the art market. And it has been seen that though performance exists within a specific time and space, it is increasingly developing an afterlive. Ushmita Sahu, director and head curator, Emami Art, is noticing that documentation through video, photography, sound and scores is being conceived as independent work rather than mere record. Sculptural elements, costumes and objects emerging from performances also carry forth their conceptual and emotional residue. Collectors and institutions are now showing greater interest in their material and archival traces, recognising performance art as both transient and collectible.

According to Farah Siddiqui, a Mumbai-based contemporary art consultant and founder of FSCA Art Advisory, collectors across the world approach performance art through rights, instruction and stewardship—increasingly through institutional frameworks that enable longevity. The genre’s commercial viability depends less on objects and more on informed collectors willing to participate in its ethical and temporal dimensions. “In this sense, performance art doesn’t resist the market, rather it compels it to adapt,” she says.

Internationally, the acquisition of performance art has been a matter of much debate and discussion. Sabine Breitwieser, former chief curator, department of media and performance art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, has been dwelling on the topic for some time now through essays and talks. In a 2019 piece, From the Modern to the Global Museum: Collecting Interdisciplinary and Non-Object Based Art, for the Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis, she mentions how acquisition of works of art based on ideas and concepts can prove to be a challenge. “How do we save documents, props, costumes, and so on, and what role do these objects play? What are the rights of co-authors and other participants? However, a fundamental characteristic distinguishes works of performative art from works of visual art: performances of these works that are constantly represented and reinterpreted by the performers and those staging them,” she writes.

MoMA was one of the pioneers in collecting and exhibiting performance art in the 1960s, later establishing a dedicated department in 2006. Tate London too began its collection of performance artworks in 2005 with Roman Ondak’s Good Feelings in Good Times (2003), and now has more than 25 performance artworks.

Since then, the gallery’s time-based media conservation team and the collection management department has been working on ways to preserve performance artworks’ continued existence as live events. In an essay titled Institutional Practices: Collecting Performance Art at Tate, the team states that these works, similar to living organisms, need certain material conditions in order to exist—these can vary from work to work.

MoMA’s purchase of Tino Sehgal’s durational performance, Kiss, in 2008 has emerged as quite a case study in recent years. “Sehgal does not allow his work to be photographed; there are no wall labels or catalogues, no official openings or press kits,” states a 2014 article, Can Performance art be Collected, on the online forum ArtsHub. “MoMA is reported to have paid $US70,000 for Kiss, and with no written contract, just the transference of the artwork to a curator orally (unrecorded), who then is charged with the role of ‘interpreter’.” The work can be lent to other institutions. “If the work gets resold, it has to be done in the same way it was acquired originally,” Jan Mot, Sehgal’s dealer in Brussels, told the New York Times in 2010.

Performance art is fundamentally reconfiguring ideas of ownership and value. Sehgal and Marina Abramović offer two important market models. While the former’s practice is deliberately immaterial, collectors acquire the right to the work through oral contracts. “What is collected is not an object but a set of conditions and responsibilities, positioning the collector as a custodian rather than an owner,” states Siddiqui.

Tate too acquired Sehgal’s This is Propaganda, with the work materialising in the gallery by a person considered as an “interpreter” by the artist. In the essay, the team states, “The conservation of This is Propaganda therefore depends on memory and body to body transmission, a notion drawn from the field of dance… . As such, the acquisition of This is Propaganda in 2005 required us to depart from our standard processes not only with regard to collection management and conservation practice, but also in relation to the transfer of title, which was enacted through an oral rather than a written contract, in the presence of a notary with the involvement of a limited number of Tate staff.”

Abramović, on the other hand, looks at a hybrid ecosystem. According to Siddiqui, while the live body remains central, her work extends into scores, relics, photos and re-performable structures. Collected items are exhibited and acquired to extend longevity of the form. The ownership of the actual performance itself, however, rests with the artist. In an article published in The Art Newspaper in 2023, Claus Robenhagen, director, Lisson Gallery which represents Abramovic states that institutions can exhibit her performances on loan, but that is done in dialogue with her in her studio. “Instead, collectors can acquire photo or video documentation; early performances are most coveted,” he adds. The Life was the first mixed-reality work ever auctioned with a 19-minute holographic performance at Christie’s London sale in October 2020, it fetched $376,326.

In India, however, the market is still at a nascent stage, with very few strong institutional acquisition programmes in place. “Galleries, biennales, and art fairs do commission performances and remunerate artists for these, but the market in our country is definitely not as mature for new media,” says Ayesha Parikh, founder of Mumbai-based contemporary art gallery Art and Charlie. “A few years ago, I was hoping non-fungible tokens would change this, but that instrument did not stand the test of time either, thanks to the volatility of the crypto market.”

Maybe this also has to do with the fact that across South Asia, performance often functions as a complementary rather than primary mode of expression. In the practices of artists like Nikhil Chopra, Sudarshan Shetty and Mithu Sen, performance intersects with other forms, expanding the conceptual scope of their practice. Debashish Paul, who works across sculpture, textile, performance and film, feels that conceptual artists are financially supported these days through grants and commissions. Though costumes from his performances have been acquired by certain institutions, the response to the genre is still not at par with that in the West. “However, in the last 25 years, collectors have been pushing their own boundaries of what constitutes art,” says Siddiqui. That slow albeit steady change might just turn the tide for performance art in the next few years.