In a letter dated January 17, 1816, the celebrated sculptor Antonio Canova revealed that he had agreed to make the Prince Regent, the future George IV, ‘an ideal group of Venus and Mars, symbolic of Peace and War’. It was a resonant subject in the aftermath of the defeat of Napoleon and was intended to take pride of place in Carlton House, London.

Carved life-size from a single block of marble, the narrow gap between the two bodies — a technical tour de force —charges the composition with energy. As one contemporary critic, Quatremère de Quincy, observed, Mars struggles ‘between love and pride’, as Venus, ‘eloquent with amorous supplication, has implanted in her companion the visible stirrings of irresolution, presaging his imminent disarmament’

(Image credit: Royal Collection Trust)

This thinly cast bronze bust of Ferdinand Alvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, is by Leone Leoni. The Duke probably commissioned it in 1555 for the long gallery in his ancestral castle at Alba de Tormes near Salamanca in Spain. It was displayed there together with busts of Charles V and Philip II, the two monarchs he served.

All three busts by Leoni are now in the Royal Collection and show the three men in identical armour. The Duke wears the Order of the Golden Fleece and a badge with a crucifix.

(Image credit: Royal Collection Trust)

François Girardon’s equestrian statue of Louis XIV was cast in bronze by the founder Jean le Pileur in 1696. It is one of four small bronzes made after the celebrated monumental original — which stood 26ft high and was cast in a single pour of molten metal on December 31, 1692 — that stood in what is now the Place Vendôme, Paris, France. It was destroyed in 1792. The dress and pose are inspired by the figure of Marcus Aurelius on the Capitoline in Rome, Italy. George IV acquired this piece in 1817.

(Image credit: Royal Collection Trust)

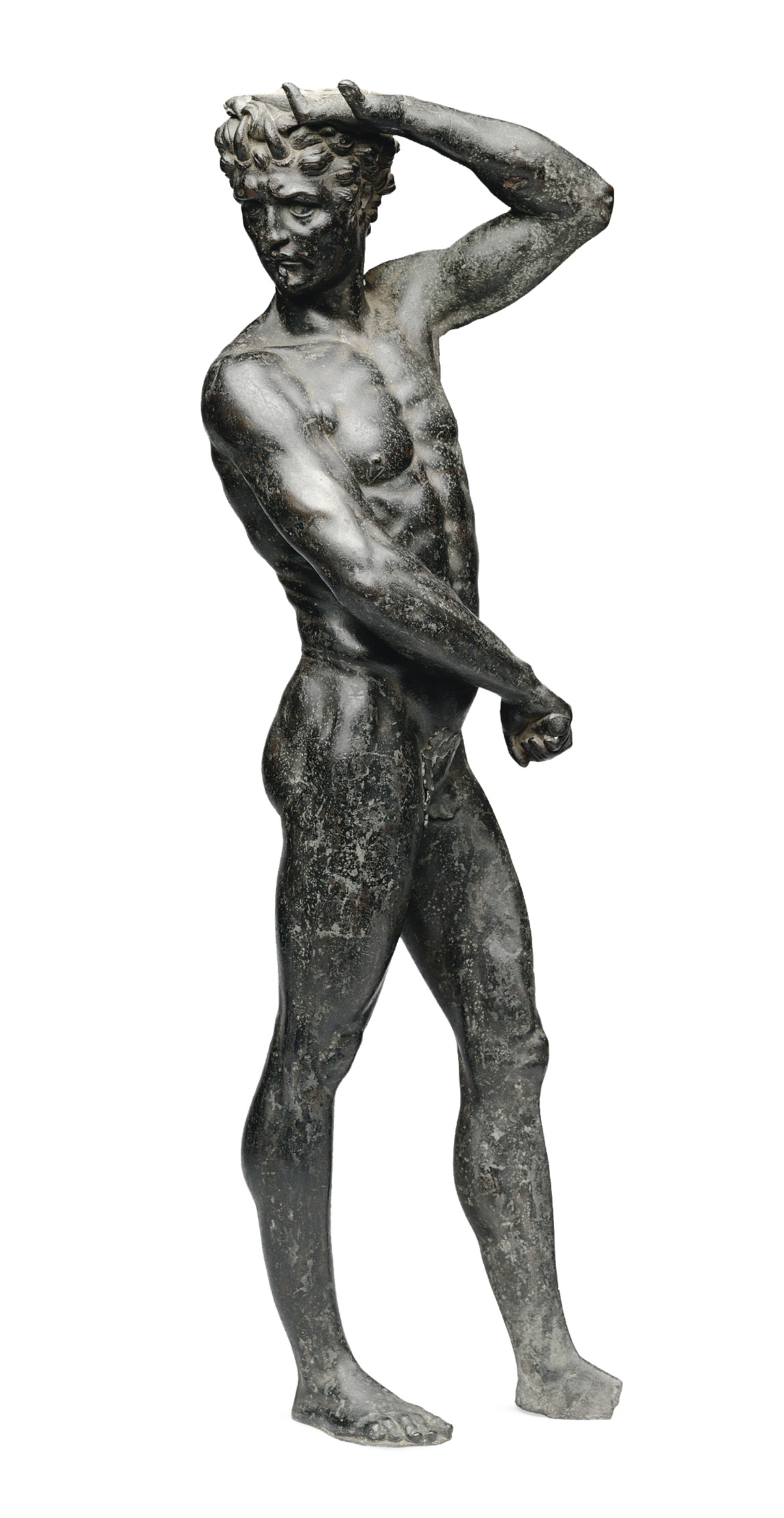

In January 1542, François I commissioned Benvenuto Cellini to redesign the porte dorée at Fontainebleau. Cellini characterised the existing doorway as ‘wide and low, [and] in their vicious French style’. He proposed to overlay it in bronze with an over-door panel of a nymph, representing the ‘fontana bella’ evoked in the name of the place, supported by two satyrs.

The project was never completed, but this is a small-scale preparatory cast for one of the latter figures. Its counterpart survives at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, USA, and the nymph tympanum — cast at full size — is at the Louvre, Paris.

(Image credit: Royal Collection Trust)

Queen Victoria was only 25 when she commissioned this portrait of herself from sculptor John Gibson as a pendant to Emil Wolff’s statue of Prince Albert as a Greek warrior. Gibson was instructed to portray the Queen in Greek dress and completed the life-size model in May 1845. The figure wears a pearled circlet or diadem.

‘My statue,’ he wrote to a friend, ‘has none of those usual symbols of a Queen — such as the crown, the royal robes and the ball and sceptre. I have tried to give royalty in the look and action.’ The sculpture was originally painted, an attempt by Gibson to revive this Greek practice, a decision that divided critics when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1847.

(Image credit: Royal Collection Trust)

Louis-François Roubiliac first made his name as a sculptor in 1738 with the statue of George Frideric Handel playing the lyre in the Pleasure Gardens at Vauxhall in London. This bust, made for the composer the following year, is based on a terracotta, now at the Foundling Museum. Handel was 54 and only recently recovered from a ‘stroke of the palsy’, which had left him partly paralysed for almost two years.

Handel kept the bust until his death and it was later presented to George III, together with the composer’s harpsichord and music manuscripts.

(Image credit: Royal Collection Trust)

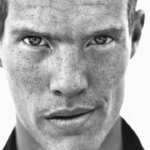

This life-size terracotta bust of a laughing child has probably been in the Royal Collection since it was first made in about 1500. It is attributed to the sculptor Guido Mazzoni, who was born in Modena, Italy. He lived in Paris between 1495 and 1516 and drew up unrealised designs for Henry VII’s tomb in Westminster.

The bust has been claimed as a youthful portrait of Henry VIII on the doubtful grounds of likeness and, for a period in the 19th century, it decorated the nursery in Buckingham Palace. The recent removal of later layers of over-paint has revealed the original colouring of this life-like sculpture.

(Image credit: Royal Collection Trust)

Personifications of the four seasons — pictured here is Spring — were probably executed in 1692–95 by the leading sculptor in Rome, Camillo Rusconi. The figures were originally created for the palazzo of the Marchese Niccolò Maria Pallavicini, but were subsequently sold to George I and were installed in the King’s Gallery created in 1725–27 by William Kent at Kensington Palace in London. It’s a mark of the admiration they enjoyed that the figures were widely copied.

(Image credit: Royal Collection Trust)

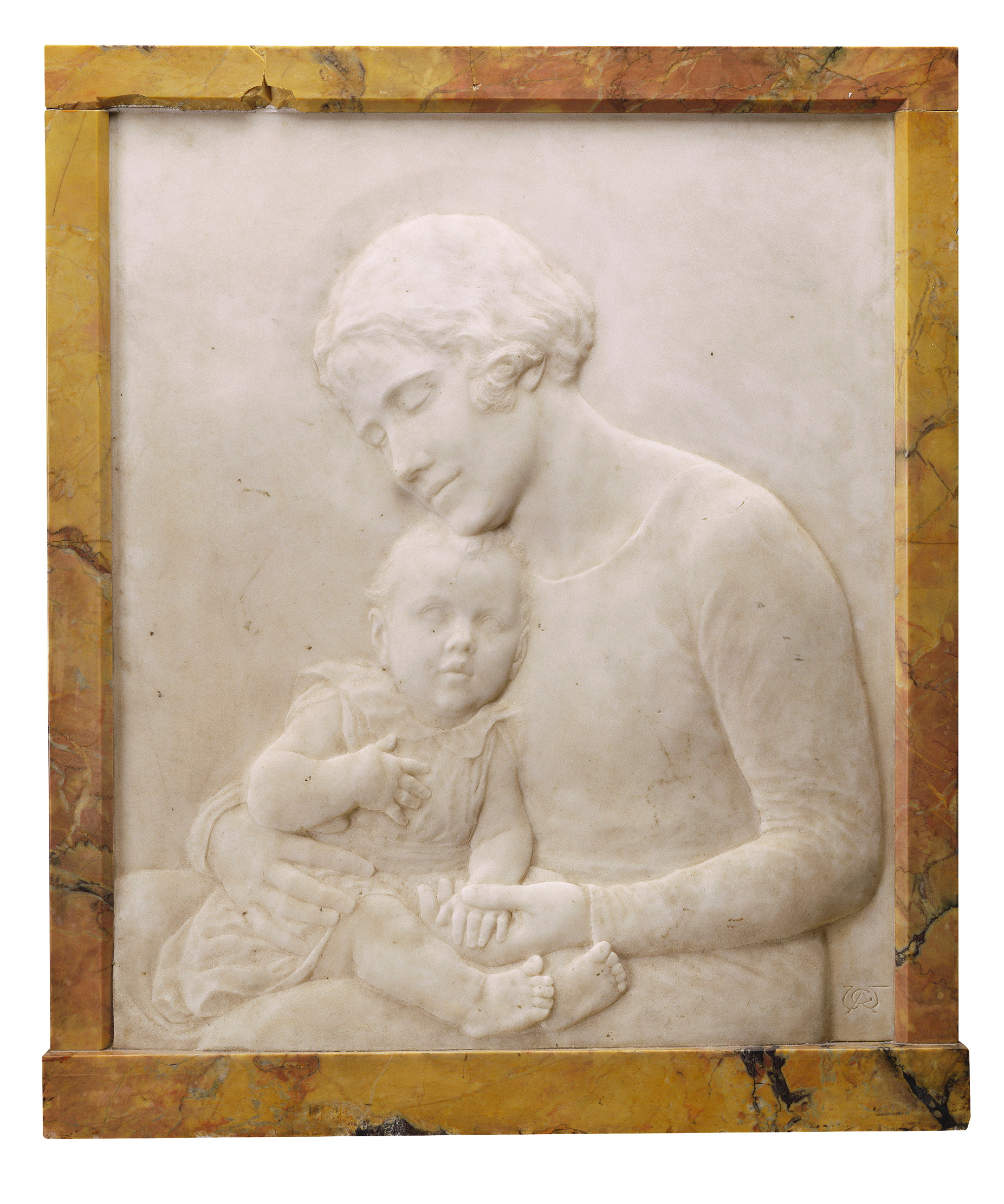

This low-relief panel in marble shows Elizabeth, Duchess of York, with her daughter Princess Elizabeth of York (later Elizabeth II), by Arthur Walker. It is a timeless image of motherhood, the sculptor having removed any jewellery or context that might date the image. The demanding technique of low-relief carving is inspired by the work of the Florentine Renaissance sculptor Donatello. Walker exhibited the completed panel at the Royal Academy in 1928.

(Image credit: Royal Collection Trust)

Enid the Fair is a unique marble version of a bust that George Frampton made in 1907 and exhibited in bronze at the Royal Academy in 1908. It is one of several idealised female portraits by the sculptor that are characterised by serene expressions, rich coiffure and medieval costume.

In this case, his inspiration was probably the story of Enid and Geraint, one of King Arthur’s knights, which was published in Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (1859–85). The square socle is also characteristic of Frampton’s work.

(Image credit: Royal Collection Trust)