Prefiguring Banky’s latest Royal Courts of Justice mural depicting a judge attacking a protestor, are centuries of art history where works have been censored or edited.

I

It could hardly be more brutal in its depiction of the administration of judicial might: a judge, arm raised, wielding a makeshift weapon, delivers his ruling, blow by blow, on the body of the accused, who lies at his feet. No, I’m not talking about Banksy’s recent (and rapidly erased) mural, which the street artist sprayed onto the side of the Royal Courts of Justice in London on 7 September. Banksy’s work, which satirically depicted an English judge in traditional wig and gown, pummelling a prone protester with his gavel as splatters of blood became the very message emblazoned on the blank placard that the protester carried, was partially eradicated by authorities three days later.

A controversial mural by the artist Banksy appeared on the side of London’s Royal Courts of Justice on 7 September (Credit: Getty Images)

Prefiguring Banksy’s work by more than four-and-a-half centuries is a marble sculpture by the Renaissance artist Jean de Boulogne (known as “Giambologna”) which portrays a scene from the Bible in which the Old Testament judge Samson “slew a thousand men” with the “jawbone of an ass”.

If Banksy’s controversial work calls to mind such potent precedents from the history of art, so too does his mural’s fate. Almost as quickly as the work was discovered on the side of the Queen’s building in the court complex, it was covered up by large sheets of black plastic and barricaded by steel barriers and guards from the HM Courts & Tribunals Service. The Metropolitan Police quickly confirmed that the work had been “reported to them as criminal damage”, allegedly in violation, it seems, of the Criminal Damage Act of 1971.

A marble sculpture by Renaissance artist Giambologna prefigures the Banksy mural by more than four-and-a-half centuries (Credit: Alamy)

The diminishment (if not complete destruction) of Banksy’s mural, a grey ghost of which still haunts the wall on which it was initially stencilled, is hardly the first time a work of art has been censored after falling foul of the law. The whole history of image-making is punctuated by episodes of restricted viewing and suppressed expression. From the smashing of icons in 8th and 9th-Century Byzantium to the destruction of Banksy’s acerbic satire on the side of the Royal Courts of Justice this week, the story of art is one routinely copy-edited by the powers that be.

Banky’s 7 September mural was partially eradicated three days later, leaving a ghostly trace (Credit: Getty Images)

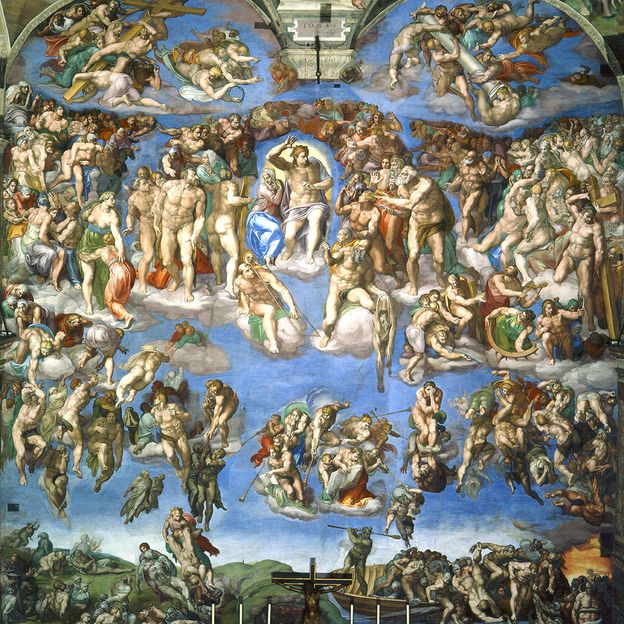

Take Michelangelo’s formidable fresco, The Last Judgment, which occupies the entire altar wall of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel. Completed in 1541, the famous work imagines the dynamic rise and fall of redeemed and damned souls as they are conveyed to heaven and hell following the Second Coming of Christ. Though it may be difficult to conceive of a less erotic subject than the bustle of bare bodies jostling for their position in eternity, The Last Judgment was nevertheless found to be on the wrong side of the Council of Trent’s decision in December 1563 to prohibit works of art that were “adorned with beauty exciting to lust”. From its first unveiling, Michelangelo’s nudes had provoked criticism by those who felt their presence “in so sacred a place” was indecent. Particular scrutiny fell on the portrayal, in the bottom right section of the fresco, of a naked St Catherine of Alexandria who appears to twerk away from St Blaise as he leans over her – his body pressed close to hers.

In order to make Michelangelo’s masterpiece comply with the new edict banning “lasciviousness” in art, the Italian Mannerist Daniele da Volterra was hired to fit the fresco’s naked figures with loincloths and vestments, earning him the nickname “Il Braghettone”, or “the breeches maker”. The result is a deft disfigurement of Michelangelo’s original vision. While modern-day restorations of the fresco undertaken in the 1980s and 90s succeeded in removing further embellishments that had been added after Volterra’s 16th-Century “corrections”, the majority of his interventions remain in place to this day.

Nudes in Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment were covered up after they were found to contravene a ban on “lasciviousness” in art (Credit: Getty Images)

In retrospect, Michelangelo’s fresco got off rather lightly. Not long after Volterra began preserving the modesty of figures in The Last Judgment with strategically positioned drapery, Protestant iconoclasts swept through the Low Countries in 1566 and attacked Antwerp’s cathedral, permanently mutilating a grand altarpiece by Frans Floris, the city’s leading artist. Floris’s fantastical Fall of the Rebel Angels, painted just 12 years earlier, depicts a saint casting out a swarm of grotesque demons. Reformers, convinced that the triptych’s imagery violated new civic laws against superstition and idolatry, ripped the wings from the work’s hinges and destroyed its two side panels. Only the central section of the triptych, relatively free of the offending iconography, survived the demolition. When Catholic rule returned 20 years later, the salvaged fragment was rehung in the cathedral, a symbol of art’s remarkable resilience.

A powerful erasure

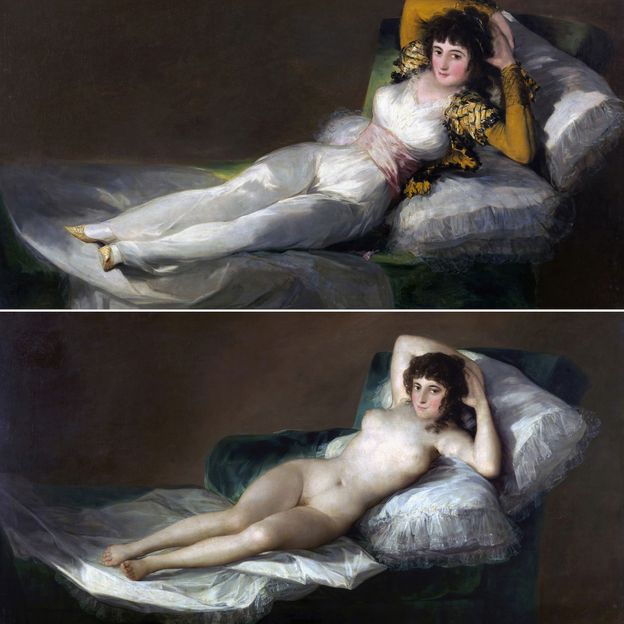

Not every work punished for its alleged violation of law has suffered irreparable damage. In 1815, Francisco de Goya’s famous pair of paintings depicting the same reclining woman in mirroring poses – one nude, the other clothed – was seized by the Inquisition and sequestered for decades, though neither was ultimately damaged nor destroyed. The works, known as The Two Majas, were painted between 1797 and 1800 and are revolutionary in their sensual portrayal of a contemporary woman gazing directly at the viewer, unconnected to any myth or narrative from history or religion.

Goya’s famous pair of paintings showing the same woman – one nude, the other clothed – was seized and sequestered for decades (Credit: Getty Images)

After the works’ owner, the Spanish Prime Minister Manuel Godoy (who kept the canvases in a cabinet with other nude paintings), was overthrown in 1808, an investigation was opened into his possession of the scandalous portraits, which were accused of breaking laws of decency and public morality. Goya was summoned to explain himself, though the record of his defence has not survived. While Goya, who held a high position as court painter, does not seem to have been punished, his works were confiscated and kept from public view until 1836 and eventually transferred to the Prado Museum in 1901.

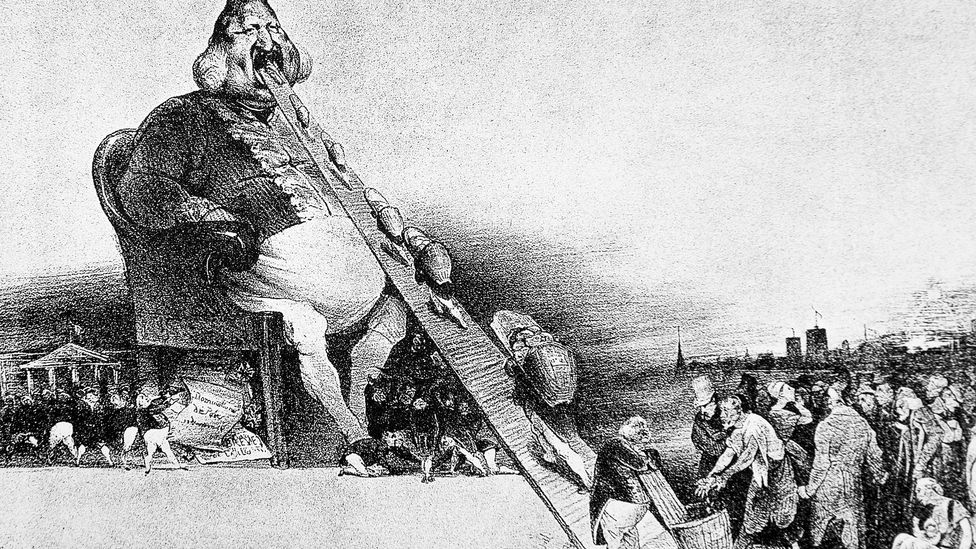

The same soft landing for both the artist and artwork would not be enjoyed by every work accused of breaking the law in the 19th Century. While Goya’s La maja desnuda and La maja vestida were awaiting their eventual pardon and release, an incendiary lithograph by the French artist Honoré Daumier was just beginning to come under intense scrutiny for inciting “hatred of the King” in violation of the law. Daumier’s work, Gargantua, published in the satirical journal La Caricature, was based on a character by Rabelais, and portrays King Louis-Philippe as a gluttonous giant who ravenously consumes the wealth and resources of his poor subjects. Enraged, the French government swiftly went after both the artist and the artwork, which had proved devastatingly popular.

Daumier’s Gargantua portrays King Louis-Philippe as a gluttonous giant – the artist was arrested and sentenced to prison (Credit: Alamy)

Daumier was arrested and sentenced to prison for six months for violating anti-sedition laws and the very stone from which the lithograph had been pulled was destroyed, preventing further distribution of the offending image. Though the government did its best to suppress Daumier’s Gargantua, copies from the first run of La Caricature survived and cheap woodcuts fashioned from the design kept the image in secret circulation.

Whether Banksy, whoever he is, will, like Daumier, be pursued by the UK government for his role in the alleged act of criminal damage to the premises of the Royal Courts of Justice, or if his controversial mural will find itself, through its partial erasure, more indelibly inscribed in cultural consciousness, remains to be seen. Sometimes what isn’t there is more enduring and more powerful than what is.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.